R. T. Raichev is a scholar of the mystery as well as a writer of mystery short stories and novels. His most recent story for EQMM, “The Other Imelda,” will appear in our next issue, November/December 2020, on sale October 20. The author’s scholarly articles regularly appear on this blog; earlier this year he examined two Agatha Christie stories in his May 13 post “The First and the Last: In the Shadow of the Uncanny.” In this post, he turns to a story that placed second in one of EQMM’s annual Worldwide Short Story Contests, “Love Lies Bleeding” by Philip MacDonald. —Janet Hutchings

“Love Lies Bleeding” (not to be confused with Edmund Crispin’s 1948 novel of the same name) is a short story written by Philip MacDonald that won one of the seven second prizes in the Fifth Annual Detective Short Story Contest sponsored by Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.* It was published by Victor Gollancz in the UK in 1950 in the annual Queen’s Awards anthology. A tale of twisted psychological suspense and perverse morality, it is the most unusual and, to my way of thinking, the most interesting story in the collection. It is also fascinating in that it manages to broach a subject that was considered taboo at the time it was written (the late 1940s) by means of subtle innuendo, repetition, and oblique suggestion.

The story opens in the drawing room of theatre designer Astrid Halmar where we see celebrated playwright Cyprian Morse sitting in a state of languid self-satisfaction, a cup of after-dinner coffee in his hand. He is waiting for Astrid to change her dress as the two are going out to a party. Cyprian whiles away the time by regarding admiringly in a mirror his “graceful, high-shouldered slenderness . . . the fine-textured pallor of the odd, high-cheek-boned face with its heavy-lidded eyes and chiseled mouth . . . the long slim fingers of the hand which twisted with languid dexterity at the tie . . .” Our attention is then drawn to the lapis-lazuli ring Cyprian wears, which, we learn, is a present from “Charles.”

Up to that moment, readers may have wondered about the existence of a possible romance between Cyprian and Astrid, but any such impression is quickly dispelled by the multiple use of the name Charles within a single paragraph. (Nine times.) Indeed it is Charles, not Astrid, with whom Cyprian is romantically and, one imagines, somewhat obsessively involved. But Astrid is in love with Cyprian. When she interrupts his reverie with a passionate embrace, his reaction is one of unadulterated horror and revulsion.**

His flesh crept . . . he felt the hairs on his neck rising . . . He backed away. She mustn’t touch him, she mustn’t touch him.

When Astrid does touch him and he becomes aware of the “dreadful warmness of her,” he takes hold of the log-pick—the scene is enacting itself beside the fireplace—and strikes her “with more than all his force.” Moments later, reason returns, and he vomits. (We are now in the realm of hysterical melodrama.) Cyprian is seen rushing out of Astrid’s apartment with blood on his clothes, the police are called, and he is arrested. Although he insists that Astrid was killed by an intruder who climbed through a window, the police remain unconvinced, and he is put on trial. There is no doubt that he is the true culprit, and his defense lawyer fears he can’t do much to help. The newspapers meanwhile scream, FAMOUS PLAYWRIGHT ARRAIGNED FOR MURDER . . . PARK AVENUE LOVE FIEND MURDER . . . MORSE, BROADWAY FIGURE, JAILED.

The general assumption—though it is never spelled out—is that Cyprian committed a crime passionnel, that he killed Astrid in a fit of jealous rage. Surprisingly, the police never ask him about the exact nature of his relationship with Astrid. Cyprian’s thoughts turn to Charles, but Charles is away, in Venezuela. Cyprian sends a telegram—“in terrible trouble, need you desperately, please come.” A telegram comes back—“hospitalized bad kick-up malaria . . . flying back immediately releases maybe two weeks . . .” (We learn that Charles’s second name is de Lastro.)***

At this point we are nearly two-thirds’ way into the story. As we witness Cyprian’s growing mental anguish, we begin to marvel at what kind of crime story, exactly, we are reading. Cyprian Morse is an antihero, unsympathetic, devious and dangerous, a candidate for inclusion in von Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis, hardly a character anyone would wish to identify with. Will the author allow him to get away with murder? If so, how? If he is punished, will it be the electric chair or prison? Or will he be declared insane and despatched for treatment at a psychiatric asylum? But wouldn’t that be too obvious? What about Charles de Lastro? Will Charles remain embedded in the background? The impossibility to predict what will happen next creates a sense of propulsive suspense, a quality lacking in most of the other stories in the collection. We read on, anxious for answers.

The trial moves forward with grim inevitability, a murder conviction seems to be a certainty, and Charles is still in Venezuela. Without doubt Cyprian’s predicament is as bad as bad can be. His appearances in court are compared to those of an “automaton” and “for unaccountable stages of distorted time his mind gazed into the pit.” But he sticks to the intruder story. Just then something startling and unexpected happens: two girls are murdered in quick succession in a manner that is identical to the brutal killing of Astrid Halmar. The newspapers now proclaim POLICE CLUELESS IN NEW SLAYINGS! MORSE RELEASE DEMANDED BY PUBLIC!

A maniac seems to be at work—a Jack the Ripper kind of figure. The police are forced to admit that all three deaths must be linked, that there is now serious doubt about Cyprian Morse’s guilt as he cannot be held responsible for the new outrages. Having reconsidered his statement about seeing an intruder in Astrid’s apartment, the police decide that he must have been telling the truth after all. (This is another, more serious, weakness of the story—why does no one raise the possibility of a copycat killer?) The district attorney withdraws the case against Cyprian Morse and he is released.

Returning home, Cyprian is astounded to discover Charles waiting for him. Charles has come back from Latin America without notifying him. From the questions Charles asks, Cyprian realizes it is Charles he needs to thank for his release. Charles only pretended to be ill. Charles had been back in New York for some time. Charles managed to get someone else to send the telegrams to Cyprian. Charles returned as soon as he read the details of Astrid’s murder—and he committed two identical murders, managing to convince everyone that there’s a serial killer at large. Charles tells Cyprian, “We sit tight—and live happily ever after . . .”

“Love Lies Bleeding” was one of Alfred Hitchcock’s choices for inclusion in his 1957 anthology Stories They Wouldn’t Let Me Do On TV. If the title speaks true—if indeed ‘they’ didn’t let him to film the story, the only possible reason must have been the nature of the relationship between Charles and Cyprian. Surprising if so, given that Hitchcock had already made Rope in 1948, which in turn was based on the eponymous Patrick Hamilton play of 1929. Both play and film deal with a similar couple and the pointless murder they commit. Indeed, the way Charles talks brings to mind the mannered callous flippancy of Brandon, the dominant partner in Rope.

A mention perhaps should be made of the story’s several dark little ironies as they more than make up for the story’s deficiencies. Shortly before Astrid makes her fatal mistake of trying to kiss Cyprian, he approvingly reflects that “Astrid wouldn’t make mistakes”—in her choice of liqueur flavors. Moments before the murder, Cyprian opens a newspaper and sees the headline CYPRIAN MORSE DOES IT AGAIN — he is being praised for his latest play. There is also the story title itself—one assumes that it refers to poor Astrid, struck down as she is about to declare her love for Cyprian, but it could also be Cyprian’s love for Charles that lies bleeding at the very end—when, rather than express his heartfelt gratitude, he accuses Charles of killing the two innocent girls “as though they were animals” and, sickened and horrified, breaks down crying, “Oh my God . . . oh my God”.

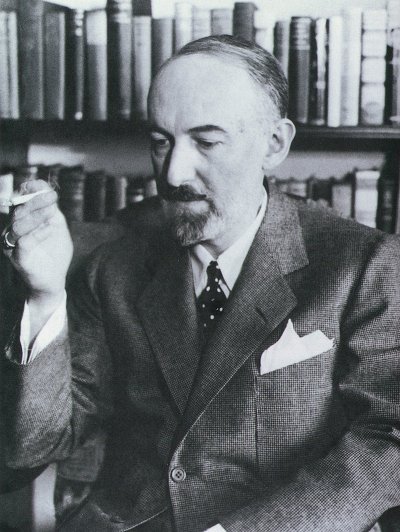

Philip MacDonald (1900-1980) is now largely forgotten, but in 1953 and 1957 he was recognized by the Mystery Writers of America and awarded the Edgar Allan Poe award for his short stories. A British author of some distinction, he wrote a number of detective novels featuring Colonel Gethryn, some of which (The Rasp, The Noose, The Maze) have been recently republished. His most famous novel is perhaps The List of Adrian Messenger which was made into a popular film by John Huston in 1963 and is still remembered for the heavily disguised all-Hollywood-star cameo performers that included Frank Sinatra, Burt Lancaster, Robert Mitchum, and Tony Curtis. As for the idea of the murderous decoy, it is still associated with—and unrivaled by?—Agatha Christie’s 1936 novel The ABC Murders.

* A single first prize went to John Dickson Carr’s “The Gentleman from Paris.”

** Cyprian’s reaction is not dissimilar to that of Mary Whittaker, the Sapphic antiheroine of Dorothy Sayers’ novel Unnatural Death, to Lord Peter Wimsey’s attempt to kiss her.

I believe I have read every Wolfe story and novel, many of them multiple times. I own most of them in cheaply printed hardcover book club editions, usually without jackets, bought at used book shops over the decades since I first read The League of Frightened Men as a teenager. The look and feel and scent of those books—the slightly musty odor, the yellowing pages, the indecipherable names of former owners scrawled inside the covers—is the first level of the authenticity I find in them. It is not, however, the most deeply experienced. That’s reserved for the brownstone itself, the building I can enter only in my mind but seem to know as well as my own home. The comfort of the red chair, reserved for clients and favored guests, with the little table alongside it to facilitate the writing of checks. The rich aromas of Fritz Brenner’s cooking. The hum of the elevator coming down from the plant rooms. The coat rack where Archie assesses visitors for possible threats, and the dining room where talk of business is strictly barred. The bright yellow expanse of Wolfe’s pajamas. The trick picture of the waterfall, concealing a peephole for spying on the office, and the big globe in the corner, for Wolfe to scowl at when he has no choice but to work. I could give tours of the place, from the basement, where Wolfe throws darts for exercise, to the roof, with its ten thousand orchids. How can I know so well a place that has never existed?

I believe I have read every Wolfe story and novel, many of them multiple times. I own most of them in cheaply printed hardcover book club editions, usually without jackets, bought at used book shops over the decades since I first read The League of Frightened Men as a teenager. The look and feel and scent of those books—the slightly musty odor, the yellowing pages, the indecipherable names of former owners scrawled inside the covers—is the first level of the authenticity I find in them. It is not, however, the most deeply experienced. That’s reserved for the brownstone itself, the building I can enter only in my mind but seem to know as well as my own home. The comfort of the red chair, reserved for clients and favored guests, with the little table alongside it to facilitate the writing of checks. The rich aromas of Fritz Brenner’s cooking. The hum of the elevator coming down from the plant rooms. The coat rack where Archie assesses visitors for possible threats, and the dining room where talk of business is strictly barred. The bright yellow expanse of Wolfe’s pajamas. The trick picture of the waterfall, concealing a peephole for spying on the office, and the big globe in the corner, for Wolfe to scowl at when he has no choice but to work. I could give tours of the place, from the basement, where Wolfe throws darts for exercise, to the roof, with its ten thousand orchids. How can I know so well a place that has never existed? Five years ago, on vacation in New Orleans, I bought a bag of beignets at the world-famous Café du Monde and carried them into Jackson Square, one of the most beautiful public spaces I’ve ever visited. I remember many things from that morning: the soaring dignity of St. Louis Cathedral against a spotless blue sky, the wandering groups of tourists, the bursts of music that seemed to come from every direction. For whatever reason, though, what sticks most vividly and most deeply in my mind is simply this: underneath every bench at the south end of the square, the pavement was marked with streaks of powdered sugar. They marked the places where people had leaned forward to bite into the sweet, airy, warm beignets while trying, and mostly failing, to keep the sugar off their clothes. When I think of New Orleans, those little piles of sugar are the first thing I think of, and they remain as convincingly real to me as the room I am sitting in now—or as Nero Wolfe’s office.

Five years ago, on vacation in New Orleans, I bought a bag of beignets at the world-famous Café du Monde and carried them into Jackson Square, one of the most beautiful public spaces I’ve ever visited. I remember many things from that morning: the soaring dignity of St. Louis Cathedral against a spotless blue sky, the wandering groups of tourists, the bursts of music that seemed to come from every direction. For whatever reason, though, what sticks most vividly and most deeply in my mind is simply this: underneath every bench at the south end of the square, the pavement was marked with streaks of powdered sugar. They marked the places where people had leaned forward to bite into the sweet, airy, warm beignets while trying, and mostly failing, to keep the sugar off their clothes. When I think of New Orleans, those little piles of sugar are the first thing I think of, and they remain as convincingly real to me as the room I am sitting in now—or as Nero Wolfe’s office.