Warm wishes from all of us at 44 Wall Street.

Warm wishes from all of us at 44 Wall Street.

What are the essential elements of the opening lines of a great crime novel? What is it that gets us hooked and keeps us reading ? What is it that makes the words at the start of Crime and Punishment or The Stranger or Chronicle of a Death Foretold to name a few, linger on through the years becoming part of our literary tradition? Can we find universal qualities in these great beginnings and thus ascertain what constitute the elements of a great beginning and perhaps use them in our own or at least recognize them in our reading.

One of the essential elements, it seems to me, is simply that the reader believes what you have to say, believes the narrator knows the story he/she is about to tell, often plunging us into the middle of things or even into the end. Here’s the start of Chronicle of a Death Foretold by García Marquéz:

On the day they were going to kill him, Santiago Nasar got up at five-thirty in the morning to wait for the boat the bishop was coming on. He’d dreamed he was going through a grove of timber trees where a gentle drizzle was falling, and for an instant he was happy in his dream, but when he awoke he felt completely spattered with bird shit.

We are drawn into this world by a matter-of-fact voice, a cool statement that contrasts with the high drama of a killing, and the kind of precise detail that only the protagonist could seemingly know (the dream, the moment of happiness, the bird shit), so that we believe or are anyway willing to suspend disbelief. All is in the assurance of the tone.

Or on the contrary the voice gains credibility by confessing they do not know all.

Thus Camus’s The Stranger begins with the lines:

Maman died today. Or, yesterday maybe; I don’t know. I got a telegram from the home: MOTHER deceased. Funeral tomorrow. Faithfully yours. That doesn’t mean anything; Maybe it was yesterday.

In other words this is a voice that we allow to take us in hand and lead us, our Virgil into the underworld.

The voice is often linked to the material. The telegraphic style in The Stranger, the white spaces between the short truncated sentences, the staccato rhythm evokes the character’s alienation.

We find this too in The Talented Mr. Ripley:

Tom glanced behind him and saw the man coming out of the Green Cage, heading his way. Tom walked faster. There was no doubt that the man was after him. Tom had noticed him five minutes ago, eyeing him carefully from a table, as if he weren’t quite sure, but almost. He had looked sure enough for Tom to down his drink in a hurry, pay and get out.

The narrator in these beginnings finds the right distance from the material with a voice that is sufficiently intimate, drawing the reader close, giving an illusion of intimacy, and yet revealing only what it is strictly necessary: a few evocative, original details; where and when we are, for example, in the beginning of Crime and Punishment:

At the beginning of July, during an extremely hot spell, towards evening, a young man left the closet he rented from tenants in S. Lane, walked out to the street, and slowly, as if indecisively, headed for the K. Bridge.

He had safely avoided meeting his landlady on the stairs. His closet was located just under the roof of a tall, five-storied house and was more like a cupboard than a room. As for the landlady from whom he rented this closet with dinner and maid- service included she lived one flight below, and every time he went out he could not fail to pass by the landlady’s kitchen , the door of which almost always stood open. And each time he passed by, the young man felt some painful and cowardly sensation, which made him wince with shame. He was over his head in debt to his landlady and was afraid of meeting her.

Here we have the details important to the plot and the character; the exact number of floors to the house, the size of the room and its location, money.

Above all we have the author’s choice of point of view. How is this chosen? In Faulkner’s Sound and the Fury, unable to decide on whose POV to use, he tried out four different ones: the three Compson brothers (like the Brothers Karamazov)— Benjy’s, the intellectually disabled man of thirty who sees without understanding, Quentin’s, the Harvard student who sets out to end his life, and Jason’s—and finally the family servant, Dilsey. These beginnings became the book where the main character Caddy never gets a point of view.

We can start from a certain distance with an unnamed third person: “a young man” as in Crime and Punishment, a closer third person where we have the first name (“Tom glanced behind him”), a first-person narrator as in The Stranger or slipped in after a few lines in Chronicle of a Death Foretold (“Placido Linero, his mother told me twenty years later”), or the very close first person of The Collector by John Fowles:

When she was home from her boarding-school I used to see her almost every day sometimes, because their house was right opposite the Town Hall Annexe. She and her younger sister used to go in and out a lot, often with young men, which of course I didn’t like. When I had a free moment from the files and ledgers I stood by the window and used to look down over the road over the frosting and sometimes I’d see her. In the evening I marked it in my observations diary, at first with X, and then when I knew her name with M. I saw her several times outside too. I stood right behind her once in a queue at the public library down Crossfield Street. She didn’t look once at me, but I watched the back of her head and her hair in a long pigtail. It was very pale, silky, like Burnet cocoons. All in one pigtail coming down almost to her waist, sometimes in front, sometimes at the back. Sometimes she wore it up. Only once, before she came to be my guest here, did I have the privilege to see her with it loose, and it took my breath away it was so beautiful, like a mermaid.

In all these examples a moment of change sets off a chain of events. Sometimes this has happened in the past, so that we ask not so much what has happened as why it did. Why is Santiago Nasar killed that day? It takes the whole book to find out. What will happen to Tom who is being followed? How does Miranda come to be Clegg’s “guest”?

The chain of events may, in a sense, go backwards or forwards. What will the mother’s death bring about in The Stranger, and why does the son not even know on what day it happened? Why is the story told in these fragmented sentences with their gaping white spaces between them? Questions are formed in the reader’s mind, events are hinted at , foreshadowed, the stone is set to roll down the hill. Where will it go?

Mystery is created. Much is unknown at the start. We have only the elements of the story. This mystery often comes from conflict.

A series of conflictual desires, opposing forces, are set up at the start. Someone wants something they have difficulty obtaining: there are elements of danger at the start of several of these novels.

From the start of Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov, we know, is heavily in debt. He wants here to avoid his landlady, to escape without having to talk to her. We have the problem of money and also Raskolnikov’s isolation, his inability to communicate or be with others (here, the landlady). We have his indecision—“and slowly, as if indecisively, headed for the K. Bridge.”—an indecision which we will soon find out turns around his decision to murder or not, to confess or not, so that the suspense lies in will he or won’t he murder; will he or won’t he be caught.

At the start of The Talented Mr Ripley, Tom wants simply to escape the man who is following him, whom we wrongly deduce is menacing Tom in some way. Instead it is Tom who is menacing Dicky’s father, we discover in a reversal.

In the first lines of The Stranger we have a series of conflicts or juxtaposition of opposites in the language itself: the death of Mersault’s mother is juxtaposed with the dry, emotionless tone, for example, like the polite, rather prissy voice of Clegg in The Collector is juxtaposed with the inherent violence of the act of stalking someone—She and her younger sister used to go in and out a lot, often with young men, which of course I didn’t like—which immediately makes us wonder about him.

Language is what happens in these great beginnings, a language which is both specific to the writer (Camus, García Marquéz), to their theme, and to the rhythm of the sentences, which gives one that telltale shiver of poetry.

The theme of the book is announced at the start. The title of the book, of course, comes even before the beginning, and sets up the first sentences and often carries the weight of what the book is about. These great crime novels are also about ideas written at a time of flux when the culture, the place, the ideas are changing, and literature expresses these new ideas.

Camus’s beginning is perhaps one of the clearest to do this for us, as it is a novel of ideas, his truncated sentences with the white spaces in between sum up the alienation of Mersault .

Thus we are drawn in by a believable voice, the mystery of the situation (a coming killing, a coming abduction), the conflict with its juxtaposition of opposites, its hopes of success, and its hints of danger that the protagonist and thus the fascinated reader faces.

Photo courtesy of Martin Edwards.

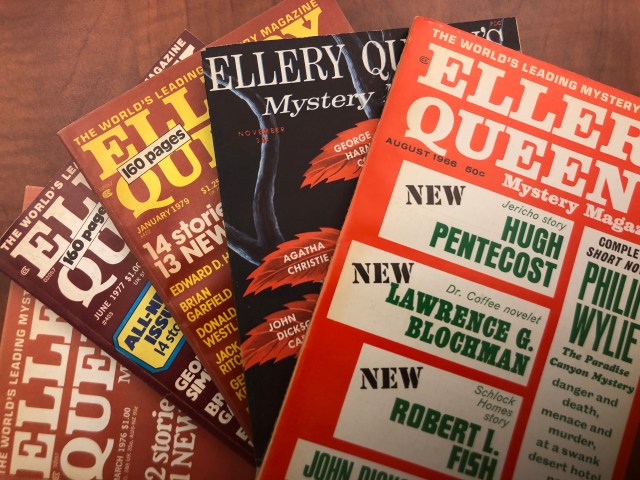

One thing I never expected to do was to be asked to sign a stack of copies of an issue of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine containing one of my stories (“The Girl on the Bandwagon”) during a mystery-game exhibition in, of all places, Shanghai. Yet that’s exactly what happened last month.

The opportunity to visit China came out of the blue. I was told that an expo celebrating “offline mystery games” was to be held in Shanghai, and I was invited to be a guest of honour. I was told that in recent years these games have developed as a new form of entertainment in China. Their roots can be traced back to murder mystery games played in the West between the world wars, but in recent years a TV show called Star Detective has become very popular in China, sparking great enthusiasm for offline mystery games. There are now over four thousand offline mystery game clubs across the country and I’m told that millions of young people are passionately enthusiastic about playing these mystery games.

Through the games, young players who previously knew little or nothing about Golden Age detective fiction have become intrigued by it. Famous writers of classic mysteries from the distant past, such as Ellery Queen and John Dickson Carr, have become well-known. So offline mystery games have caused young Chinese people to become interested in detective fiction more generally.

This boom in the murder-mystery game industry was the catalyst for the convention. The expo was the first of its kind and the major exhibitors, I was told, would be game producers and resellers from all over China. They would bring their games to the venue and demonstrate the story to potential buyers and players. During the expo, visitors would be able play the game at each booth for free.

The aim of the expo was not only to publicise the games but also to raise awareness and knowledge of mystery literature and cultivate the culture of the detective story. I was asked to give a lecture on Golden Age mysteries, and also, because I’ve written a number of scripts for interactive murder mystery events in Britain, to give a short talk about them. My fellow guests of honour included Japan’s Shimada Soji, and France’s Paul Halter—and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, I’m glad to say, had a highly visible presence. The magazines flew off the shelves and Janet Hutchings addressed delegates via a prerecorded video. There was also an exhibition of rare signed books by the likes of Ellery Queen, John Dickson Carr, and Rex Stout.

Photo courtesy of Martin Edwards.

The consultant to the exhibition, Fei Wu, a young detective writer (he has contributed to EQMM, while CITIC Press has just published his first novel, The Lost Winner), proved an admirable host, and Soji Shimada, Paul Halter, and I each took part in a separate mystery game. These games can run on for seven hours, although ours was limited to a couple of hours; playing it in the company of five young Chinese mystery fans and the game’s designer was like no other game I’ve ever encountered. There is a lot of role play and interaction between the players, and this social side to the game is evidently part of its appeal.

Paul Halter and I were particularly struck by the youth of the mystery-game fans, and we lost count of the number of selfies they took with us. Of the thousands of people who attended the expo (I gather that up to 5,000 were present on the Saturday alone) hardly any of them were over the age of thirty-five, and that included the Chinese crime writers, editors, and publishers I met.

I enjoyed myself enormously in Shanghai. And I do believe that the more we all do, as writers and readers, to get to know and understand each other, the more we’ll enjoy and appreciate each other. And the more likely it is that, even in an age where divisions sometimes seem appallingly deep, we’ll come to realise that—as the organisers cogently expressed on the mementos given to the guests of honour—we’re all part of one world.

Commemorative statue sent to EQMM by Fei Wu.

“There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Ana’s that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen. You can even get a full glass of beer at a cocktail lounge.”

Raymond Chandler called it in the opening of his story Red Wind above. He mentions the Santa Ana Winds, which are something we have to contend with here in California for several months of the year. Also known as the Devil Winds, they’re usually accompanied by low humidity and create extremely dangerous fire conditions. So, in an effort to prevent fires both SoCal Edison and Pacific Gas & Electric have been doing preventative safety power shut-offs to large swaths of both southern and northern California respectively.

Because my wife Amy and I live in a fire-prone area we’ve had to deal with these power cut-offs twice recently and possibly more by the time this is published. And let me tell you, it’s not fun. I think we’ve come to take electricity and all it provides for granted, both in general and in how it relates to our writing.

It’s a little mind blowing to realize how dependent we are on electricity for the creature comforts, but in particular how much our writing has become dependent on electricity. Sure, we could write with pen and paper, but how long could we continue and how much would it impact what we write and how we edit?

During the recent nearby fire, we lost power for several days off and on over a week because of the preventative shut-offs, which caused us to lose internet, cell-phone service, and even our landline phone.

Some of the other things we had to do without: refrigeration—and once the power came back on we ended up having to throw out tons of food. No TV or computers. With flashlights we could read a little at night but I’m no Abe Lincoln wanting to read by candle or flashlight. Gas stations weren’t pumping gas. If the power had been off longer we might not have been able to get natural gas either. As it was, we couldn’t heat the house, but the water heater stayed warm. No cooking. And, of course, no writing.

The whole area was dark, which leads one to be concerned about the possibility of looting as well. It was also difficult not knowing what the fire situation was as we couldn’t check the internet. We’re so connected for so many things these days but without internet and, since the cell and landline phone service was out too, we really felt “blind” and disconnected. You’re really on your own. That wasn’t a good feeling.

Under normal circumstances, my wife and I can communicate at almost any time, especially in an emergency . . . or so we thought until this recent outage when everything went dead. She takes the train to work and not too long ago got stuck in a flash flood. If it weren’t for e-mail, texting, and voice calls on the cell phone we would never have been able to communicate and I wouldn’t have been able to pick her up as the train had stopped running. If this had happened during these current outages, when cell and landline service went off, she would have been stuck.

So, while we can still do things the way our parents and grandparents did, and even we did in the olden days, we’ve become accustomed to the plugged-in conveniences of modern life. We might still like to read a paper book or eat a slow cooked meal when we get tired of microwaved food. And we still need to “unplug” sometimes, turn off the cell phone, log out of Facebook, and even take a break from writing and let our minds drift. But we want to do it at our convenience.

In the ye olden days, we did things differently and in a pinch we can go back to those ways, but it isn’t the same once you’ve tasted the “good life” of the modern world. When I began as a writer I was on a typewriter. And when PCs first came out I thought who needs this? I was happy working on the latest incarnation of a typewriter, the Selectric, that had a ball that you could actually change fonts with. Wow! And moving a paragraph from page 3 to page 93 was simple. All you had to do was get out a scissors, snip snip snip, move the paragraph, Scotch tape it to the new page, white out the lines, Xerox it and hope the lines where it was taped didn’t show too badly. So who needed a computer to write? One day, my then-writing partner got one of the very early PCs and I went over to his house and saw him magically move that paragraph from page 3 to 93: I was hooked. I was the second person I knew to get a personal computer, one of those fancy-schmancy things with two floppy drives, no hard drive, and a thimble full of memory. But it was, indeed, Magic. No literal cutting and pasting. No Liquid Paper (“Wite-Out”). It was liberating.

Not only have we become uber dependent on computers, we’re also dependent on “mini computers,” like cell phones with Skype and Uber and Waze. We can’t go anywhere or do anything now without our cell phones. Can’t find out what our friends and relatives are doing or where our kids are hanging out. Can’t find a restaurant or a movie or a parking space—or check on fire and evacuation info. Can’t write.

These electric and electronic conveniences have made our lives easier and have also made writing easier. You no longer have to go to the library and spend hours looking through books and microfiche to dig for information and sometimes come up empty. Now you can do most of your research online. You can do it at 3 a.m. when the library is closed. You can interview someone in France while sitting in the comfort of your own living room.

The internet also helps writers be more connected, to network and share ideas and tips (like on this blog). Writing used to be (and still is) a lonely profession. But social-media websites have made it possible for writers to gather around the virtual watercooler and shoot the breeze or commiserate. I missed that when the power was off.

Computers have changed the ways we work. In some ways they’ve freed us to be more creative. We’re able to be more flexible, change things and rewrite at a whim (like my example above about moving a paragraph). We also have spell checkers and grammar checkers and programs that will keep track of your characters and word count.

The creative process is still difficult. No matter how many bells and whistles we have, there is still the daunting process of the actual writing. And whether you’re writing on an iPad or a stone tablet, it’s still difficult to express those ideas and get them out into the world. Facing a blank computer screen isn’t any easier than facing a blank piece of paper. A writer still needs skill and inspiration to work. But all these modern conveniences really do make the process easier.

I didn’t get any writing done while the power was out. I suppose I could have tried to write with pen and paper but when you’re worried about running out of battery power and trying to get a radio signal so you can find out where the fire is and what areas are evacuating, you don’t have a lot of concentration to write. Besides, I like writing on those modern conveniences—and my handwriting is so bad these days I can’t read what I’ve written. Maybe I should have been a doctor. . . .

So, while all of these devices have made life easier in general and the life of a writer easier in specific, we’ve also become so dependent on them that it becomes very difficult when we don’t have access to them. Of course, our pioneer forbearers would laugh at what we find inconvenient and a hundred years from now our great grandchildren will think about how primitive we were.

We are so very grateful to you, our readers!

The secret to a good magic trick is never how the magician pulls the proverbial rabbit out of their hat. The real trick is getting the audience to look at anything other than the hat. The distractions. You know, I assume. Truth is, I have no earthly idea. I have never successfully completed a magic trick. Nor do I make a habit out of messing around with rabbits. I do, however, know a thing or two about teaching and a little bit about writing mysteries.

Teaching isn’t much different from magic. We spend most of our time attempting to trick kids into learning. And most of our tricks come from the world outside of school. The best teachers divine their inspiration from the “real world.” And, I would argue, mystery writers are no different. Tricks of the craft—tropes like the red herring or the MacGuffin or the mystery box—are utilized in mysteries not simply because they are convenient to a plot. They have become tropes of mystery fiction because they exist in real mysteries.

While many of us may not see these elements in real-life mysteries, that is not because they are not there. Much more likely, we don’t see them because they get weeded out in the telling. Newspapers and other media outlets are often charged with relaying the facts, filtering out the more confusing elements that, at one point, turned a tale of crime into a mystery. But one outlet preserves the narrative form of true crime. And that outlet is the true crime podcast. Like many of the best true crime books, the true crime podcast is all about the telling of the story. Which means, they are filled with all the elements of a good mystery.

Take, for instance, the MacGuffin. The MacGuffin, just to review, is a term made famous by Alfred Hitchcock. In simplest terms, it an object, person, or event in a story that exists (within the story) merely to ignite the plot. The best example in fiction is The Maltese Falcon. The “stuff dreams are made of.” The bird from the book/movie to which it provides the title is really irrelevant. But a story erupts around it and because of it.

One of the best podcast examples of a MacGuffin occurs in Bear Brook. From New Hampshire Public Radio, the podcast begins with four bodies discovered in two barrels in the woods of Bear Brook State Park. Most mystery readers/writers would never suspect the actual bodies in a murder mystery to, themselves, turn out to be a MacGuffin. But, in the case of Bear Brook, that is exactly what happens.

Between amateur sleuths and geologists and genetic genealogy and even a hot-air balloon, the story of searching for a killer becomes far more fascinating than the decades-old killing itself. And while it may sound dismissive to call human beings MacGuffins, their case led to the science used to capture the Golden State Killer. So as heartbreaking as it is to hear [SPOILER] that some of the bodies are never identified, the investigation is riveting and very, very important.

Another clear-cut MacGuffin used in a podcast shows up in the opening minutes of S-Town. Created by the producers of Serial and This American Life, S-Town follows Brian Reed’s investigation of a murder in Woodstock, Alabama. What Reed almost immediately learns, however, is that this murder is nothing more than a MacGuffin. And S-Town is no murder mystery. But what it becomes is an exploration of a true life mystery box.

As J.J. Abrams famously discussed in his TED Talk, the mystery box is that element of the unknown which, never fully opened, offers limitless potential suspense and wonder. So, in a case like the TV show Lost, the mystery box of the island only reveals a handful of its heavily guarded secrets. The real story becomes the people on the island, and their juxtaposition to the infinite suspense of that unopened mystery box allows the viewers to delve deeper and deeper into their characterization.

S-Town shows us what this looks like in real life. The town of Woodstock, and more importantly, the central character of John B. McLemore become mystery boxes. And [NO REAL SPOILER HERE] we never find out all of their secrets. But something about the endless possibilities make the journey feel like a mystery, even after we have left the murder MacGuffin way back in our rearview.

Which brings us to the hallmark of any good mystery: the red herring. The red herring is the clue meant to distract us. Best personified by the character, Red Herring, in A Pup Named Scooby-Doo, the red herring leads us down the wrong path. Just as Fred Jones always suspects Red of the crime, what the reader/viewer discovers, along with the Scooby Gang, is that Red was nothing more than a distraction. The sleight of hand meant to take our focus off the hat.

One of the classic examples of red herrings galore in a podcast is during the first season of Up and Vanished. Famous for the fact that host Payne Lindsey actually helped solve the case in question, Up and Vanished investigates the case of Tara Grinstead. While the attention Lindsey brought to the case finally helped solicit a confession, the early episodes of the podcast are rife with red herrings. A business card was left in Tara’s door, a medical glove was dropped in her front yard, and cadaver dogs hit on remains down a local trail called Snapdragon Road. These are all salacious leads, taking Payne Lindsey and his listeners down rabbit hole after rabbit hole. None of which lead to the real culprit.

An even better example may come from the second season of Catherine Townsend’s podcast Hell and Gone. Both seasons are wonderful, but the second season’s focus on the mysterious death of Janie Ward at a party gives us a textbook example of how to utilize red herrings. [MAJOR SPOILERS] Very early in the podcast, Townsend drops hints and mentions at what appears to be the actual cause of death: rubbing-alcohol poisoning. At the party, a punch was made with fruit soaked in rubbing alcohol. Janie Ward was said to have been eating some fruit. And rubbing alcohol poisoning turns out to be a highly likely and interesting explanation. But what Townsend does in her telling is cloud our vision of one interesting explanation with multiple red herrings. And, take note, each is a little more extravagant than the last, all serving to distract us from the truth. We get tales of high-school drama, a possible town cover-up conspiracy, and even conflicting autopsy reports. The red herrings are used masterfully to keep our attention, before the curtain gets ripped back and there was our culprit all along.

So while the best place to look for a clinic on writing mysteries will always be the best mystery fiction, the lessons I find myself using over and over again in my own writing often come from true crime podcasts. My recent story in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, “Stray Dogs,” pulls heavily from a local unsolved mystery and multiple bits and pieces from podcasts. I am obviously going to make you read it to look for evidence of that fact. You know, if it’s even a fact, at all. Look at anything other than the hat, and all.

It is an exciting time to be a writer in this brave new world of self-publishing and expanding markets. With the advent of several online platforms, including Amazon, Kindle Direct Publishing, Kobo, iBooks, and Smashwords, authors no longer need to rely on traditional publishers to get their work out into the world.

A good place for new (and even established) authors to get their work printed and do some networking is through small independent publishers and their anthology or magazine projects. Who are the individuals taking the time to create these books? What motivates them, and is there any profit margin? Where do they see the future taking them? In order to get a sense of the people behind the anthology and indie-magazine covers, I asked a few publishers these very questions.

Azzurra Nox is the force behind Twisted Wings Productions, and she has a short story horror anthology coming out in February 2020 called Strange Girls in Horror. She launched her company in 2015, with her first Women in Horror anthology My American Nightmare printed in 2017.

Azzurra Nox is the force behind Twisted Wings Productions, and she has a short story horror anthology coming out in February 2020 called Strange Girls in Horror. She launched her company in 2015, with her first Women in Horror anthology My American Nightmare printed in 2017.

Nox says, “I work as a graphic designer for my day job. Which I guess helps with being able to have an eye to choose the most appealing book covers for the anthologies I put out.”

As with most of the publishers I interviewed, her ventures are more of a labor of love.

Nox explains, “By far, My American Nightmare: Women in Horror Anthology has been the most successful I’ve printed, but all profits made were used to invest in the second anthology that I’ll be printing. All money made gets invested back into new projects that will showcase a whole new slew of women writers.”

When asked why she does what she does, she says, “I look forward to putting together more Women in Horror anthologies in the future! By far, those have been the most fun to do, because writing is a solitary task—but when you work with other authors then you’re able to forge new friendships, and I think it’s important for writers to have friends that are writers too, because they will be able to understand many of your struggles that your nonwriter friends may not comprehend.”

Alec Cizak is the brainchild behind Pulp Modern, a fiction journal that publishes crime, fantasy, sci-fi, horror, and even delves into topics that are typically taboo. Though he wishes he was born in the era where pulp fiction was a profitable venture, he teaches literature and composition to pay the bills. The current issue of Pulp Modern features futuristic crime stories. To date, he’s published fifteen issues of the magazine.

Alec Cizak is the brainchild behind Pulp Modern, a fiction journal that publishes crime, fantasy, sci-fi, horror, and even delves into topics that are typically taboo. Though he wishes he was born in the era where pulp fiction was a profitable venture, he teaches literature and composition to pay the bills. The current issue of Pulp Modern features futuristic crime stories. To date, he’s published fifteen issues of the magazine.

Cizak says, “I started publishing Pulp Modern because I didn’t see any journals at the time that brought the major genres together. I also didn’t see any big-time publications publishing riskier stories, so I felt there was a need for a market that could take chances since no advertising dollars were on the line. As time went on, I decided to continue publishing Pulp Modern because it provided a place for new writers to get their work in print. I suppose it’s like a farm team in baseball. Writers get their work in Pulp Modern and then move on to get agents and contracts with the Big Five and all that good stuff.”

When asked about profitability, he says, “This is, financially, a losing venture. The recent Tech Noir issue cost about six hundred dollars to produce. It’s generated about fifty dollars in sales, and I doubt that number will even double. This is a labor of love. The independent pulp-fiction community has had lags over the last ten years or so, moments where there were almost no markets for new writers, and I’ve gone through periods where I thought I would quit, but enough people would write to me and insist I keep Pulp Modern going that I gave in every time and got back to it. There are many, many writers out there. Some of them are really good, and they don’t have connections in the publishing world. A journal like Pulp Modern is there to make sure those unheard voices are heard.”

Lewis Williams works full time in the industry, saying “books, editing, and writing are my day job.” He is the founder of Corona Books UK, and claims he can’t take all the credit because he has friends, family, and business partners who help quite a bit. Corona Books UK was started in 2015, and have published The Corona Book of Ghost Stories, The Corona Book of Science Fiction, and three volumes of The Corona Book of Horror Stories.

Lewis Williams works full time in the industry, saying “books, editing, and writing are my day job.” He is the founder of Corona Books UK, and claims he can’t take all the credit because he has friends, family, and business partners who help quite a bit. Corona Books UK was started in 2015, and have published The Corona Book of Ghost Stories, The Corona Book of Science Fiction, and three volumes of The Corona Book of Horror Stories.

He started his small press as, “a desire to seek out, celebrate, and give a voice to some of the writing talent out there that mainstream publishers are apt to ignore. Genuinely, there’s so much writing talent out there in fields like horror and science fiction. For our last horror anthology we received over 800 short-story submissions, and whilst it’s true not all of them were of the standard we’d want to publish, there were still far more stories we’d have been very pleased to publish than there were room for in one book.”

As for profitability?

Williams says, “It’s true to say we’re doing this more for art’s sake than for profit, at least at this stage, and if you genuinely counted all the hours that went into producing something like The Third Corona Book of Horror Stories from 800 submissions, profit would just be a distant spot on the horizon!”

Future plans include “The Fourth Corona Book of Horror Stories for 2020 and, as long as my heart’s still beating, a horror anthology every year after that! We also plan to do more with science fiction and other genres—and will be announcing plans soon.”

Jonathan Lambert is the founder and editor of Jolly Horror Press, with a new anthology Accursed available December 10, 2019, and Betwixt the Dark & Light and Don’t Cry to Mama now available on Amazon. He works as a senior executive at a U.S. Federal Government Agency, and spends his weekends working on his writing and anthologies. His press specializes in comedy/horror.

Jonathan Lambert is the founder and editor of Jolly Horror Press, with a new anthology Accursed available December 10, 2019, and Betwixt the Dark & Light and Don’t Cry to Mama now available on Amazon. He works as a senior executive at a U.S. Federal Government Agency, and spends his weekends working on his writing and anthologies. His press specializes in comedy/horror.

Lambert says, “after a few years of experience selling short stories to anthologies, I just decided I could do a better job. Provide better customer service, and be more author friendly. I could also create a press dedicated to horror/comedy. Finally, these stories could have a home. I just needed the name, and one day Jolly Horror Press just popped in my head. The rest is history.”

Lambert explains, “I use the words ‘labor of love,’ and that’s true. I don’t care if our books are profitable. I’d love it, of course, but it’s not going to stop us from producing quality anthologies. I do have that day job, you know?”

Natalie Brown just recently released the Scary Snippets Halloween Anthology, and is a stay-at-home mom with three small boys. She opened Suicide House Publishing on July 28, 2019. Scary Snippets Halloween was its second debut publication; with the first being Calls From The Brighter Futures Suicide Hotline (hence the company name) released on September 19th.

Natalie Brown just recently released the Scary Snippets Halloween Anthology, and is a stay-at-home mom with three small boys. She opened Suicide House Publishing on July 28, 2019. Scary Snippets Halloween was its second debut publication; with the first being Calls From The Brighter Futures Suicide Hotline (hence the company name) released on September 19th.

Brown says, “I became a member of the online horror-writing community in February of this year. During that time, I have had so many ideas for future collaborations and anthology topics. Since then, I have been offered so many amazing opportunities as an author; I really wanted to pay it forward. It means a lot to help other people’s dreams come true like others did for me.”

Suicide House currently has a call out for Christmas microfiction, and Brown says, “one plan we have is to create a market for people to take their microfiction holiday pieces. We plan to have collections for every holiday, with Christmas well underway currently. Also our insect-horror anthology Death and Butterflies will have two installments released in early 2020, with the first being set to release January 1st.”

Valerie Willis works as the lead typesetter for Salem Author Services serving under the main imprints of Xulon Press and Mill City Press and also runs Battle Goddess Productions. She has been hosting the Demonic Anthology since 2017, and currently has three Demonic books in print.

Valerie Willis works as the lead typesetter for Salem Author Services serving under the main imprints of Xulon Press and Mill City Press and also runs Battle Goddess Productions. She has been hosting the Demonic Anthology since 2017, and currently has three Demonic books in print.

Willis says, “I wanted to traditionally publish in the beginning. It was through conversation with several literary agents that I discovered some very important things about myself and my writing. First off, I blend and mix so many genres that my work can be difficult to market and target the right audience. Secondly, they gave me resources and advice and set the expectation that my story was good, but if I wanted to self-publish, I would have to become a small press or entity that wasn’t afraid to push out the same quality look and feel of the big publishers. With all of the good advice, I moved forward with the reassurance that this had been my fate. Learning so much, and after much practice, I eventually opened up Battle Goddess Productions so that I may publish, push, and help other authors like so many had done for me.”

Willis says her anthologies are different because, “we are an unexpected blend, with paperback books that are a little more decorated inside than the average book. Authors are encouraged to blend and mix genres and we do our best to let the readers know what to expect.”

As for profit, “right now, it’s a tight fit. Most of the profit earned is rolled right back into the business to maintain sites, pay for subcontractors, and mostly into the advertisement and marketing. We are not pushing out to our full potential, considering I am technically still a one-man-army raising a family with a day job. Still, we sell books constantly and steadily even when we are not pushing for all our titles at once.”

Willis has no plans to slow down, saying, “it would be wonderful if in the future I could even provide several imprints to include genres outside the speculative-fiction focus that we currently have built. If you need something dark, fantasy, or even off the beaten path, know that you will definitely find it here at Battle Goddess Productions.”

As an author with stories in all of these anthologies, I personally appreciate the efforts of the individuals behind the pages and the time and attention they pay to their passion. It truly is an exciting time to be a short-story writer!

A couple of years ago I was lucky enough to be hired for what I consider a mystery buff’s dream job: doing research on true crimes for a television series. I was essentially getting paid to find and read all about murders, how they were committed, and how they were investigated. Working from home, I spent hours combing through online newspaper archives and doing Google searches on my computer. (The words ‘‘police’’ and ‘‘baffled’’ proved to be the best search terms for the latter activity.)

I found a surprising number of grisly stories: a man out for a walk killed by crossbow, a woman dismembered and stored in the attic of a Northern Ontario cottage, a couple murdered by their troubled son, who threw the bodies into the family truck before driving to a restaurant called Moxie’s and consuming a 10-ounce steak dinner along with five Blue Zen martinis.

But one of the most interesting cases I looked at was the killing of Maria Wong.

Originally from Hong Kong, Ms. Wong, 44, was well known in Toronto’s Chinese community, and well liked. Part owner of a popular Chinatown restaurant, she was described by everyone who knew her as chatty and always smiling. She not only donated to charities but was also the kind of woman who would bring treats to the English classes she attended at the local library.

On the afternoon of February 11, 1999, she could have had no idea that she was being followed home from her English class, then again when she went out later to buy a take-out meal for the family dinner. Inside the car was a motley crew of four, a man named James Pierce, his girlfriend, a former prostitute named Lisa Bateman, and a pair of teenagers, Chris Ortiz and Norman Figueroa.

No sooner had Ms. Wong pulled into the garage of her suburban house for the second time than she was attacked. With Figueroa acting as lookout, Ortiz stabbed her several times in the neck and throat, frustrated by how long it took her to die. The pair then drove off in Ms. Wong’s car, a dark green CRV, leaving it a few minutes later at a nearby strip mall.

Ms. Wong’s elderly father-in-law was the only person at home that evening, but he heard nothing. Her husband of twenty-four years, Shu Kwan ‘‘Johnny’’ Wong, was at work at Champion’s Off-Track Betting, a business he co-owned. A seventeen-year-old niece, visiting from Hong Kong, was at night school. Offered a lift home by a fellow classmate, it was the two of them who discovered Maria Wong’s lifeless body in the garage several hours later. The classmate, Jason Yu, called Johnny Wong first. He returned to the house right away, and was visibly distraught at the sight of his dead wife. Then the young man called York Region Police.

Johnny Wong was openly and immediately cooperative with the police, signing consent forms that allowed detectives go through his cell phone and financial records. But as the weeks passed, they had little to go on.

Ms. Wong’s murder in a quiet suburban neighbourhood seemed random and inexplicable. If the motive was simply robbery, why hadn’t the attackers gone into the house to search for valuables? And why had the stolen car been so quickly abandoned so close by? The handful of leads that came through Crime Stoppers tips proved to be dead ends; all of the suspects had alibis. Four months after the murder, headlines described the slaying as ‘‘still puzzling’’ the police. By then, Johnny Wong had sold the family house and his car and moved back to Hong Kong.

The only real clue the detectives in charge of the case, Les Young and Bill Sadler, had were the recollection of various neighbours, who said they had noticed two “swarthy” men on the street that night, talking on cell phones.

That left Sadler with the unenviable task of combing through 30,000 cell-phone calls, while his colleagues carried on with the mostly fruitless legwork. Working late each night and over the weekend, Sadler went through the list, checking each number, one by one. What finally caught his attention was an absence: several phone calls back and forth from Johnny Wong to a particular number, which suddenly stopped after the 11th of February. That number belonged to a man named Andre Jones, who worked as a bouncer at Champions, and was the first real clue that Ms. Wong’s death may not have been as random as it initially seemed.

In many classic murder mysteries, the co-conspirators agree not to see each other for a while to avoid suspicion. In this case, it looked odd.

More cross-referencing led Sadler and Young to calls made by Jones to Pierce. Cell-tower records showed that not only was he in the area on the day of the murder, but was busy making calls to Jones, Ortiz and Figueroa. Pierce happened to be facing charges for assaulting Bateman, which led to led the police to her. She wasn’t very good at cooking up any kind of innocent explanation, which left the detectives even more curious about her. They got a warrant to tap her phone.

But a real motive was to be found in Johnny Wong’s financial history. He clearly liked to gamble, and usually lost. Deeply in debt, it was notable that his wife’s $600,000 life-insurance policy would easily take care of all his problems and leave a big chunk left over for him to start a new life.

What really brought the story together was Bateman’s penchant for boasting. She was recorded telling a friend that she planned to write a movie script based on her involvement in the killing, and hoped it would make her famous.

It turned out that Wong had originally hired Andre Jones to kill his wife for him—he had even gone shopping at Walmart for a red tracksuit that wouldn’t show blood spatters—but he lost his nerve and got his friend, Pierce, to do it instead. Pierce hired Ortiz and Figueroa with the promise of a $2,000 payout. He also got rid of the murder weapon and the bloody clothes. Wong was eventually extradited from Hong Kong, tried, and sentenced to life. Pierce got sixteen years for conspiracy, Jones and the two younger men, life with the possibility of parole after 14 years.

Case closed.

What I found fascinating about this terrible tale, a tale of the ultimate betrayal of an average, middle-aged woman, was that simple mistake on the part of Johnny Wong. The other thing was the character of Lisa Bateman. She agreed to testify for the prosecution in return for being put in a Witness Protection Program and wasn’t charged. But she kept telling people she was in the program so got kicked out.

The television series never did get off the ground, but I held on to my notes with the idea that someday I might write a story about it, a story about the killing of an innocent woman from someone like Bateman’s point of view.

There was something about her involvement that underlined the fact that most murders are committed by ordinary, run-of-the-mill people, people who make mistakes, who aren’t very smart, who dream of being famous. People who somehow combine within themselves the human and the monstrous. It may not be the stuff of the kind of police procedural you can’t put down, but in real life, it’s them who kill.

With Halloween just hours away, I thought I’d try to answer a couple of questions that sometimes come up at the writers’ conferences and conventions we attend: 1) Does EQMM publish stories involving the supernatural? And 2) If not, why not?

The answer to the first question is simple: Yes, but only very infrequently.

The answer to the second question—which seems to be demanded by the rarity of our excursions into supernatural terrain—is complicated. It begins with tradition. EQMM was launched with the aim of bringing together between common covers a wide variety of different types of crime and mystery fiction. Founding editor Frederic Dannay boasted about this in his first issue, announcing that readers would find stories of the “hardboiled” school, the “modern English school,” the “modern American school,” and even stories fusing humor and mystery. He was right to point to the variety of the new magazine’s content as one of its pivotal features, for he would break new ground by publishing gritty, realistic stories alongside classical mysteries and other fare. It’s my view that in bringing a number of different subgenres together in EQMM, Dannay played a crucial role in weaving mystery and crime fiction together into the overarching genre we have come to celebrate today (at events such as Bouchercon, which turns 50 tomorrow, on Halloween, as the 2019 convention begins in Dallas!). But the supernatural crime story, which has become so popular on today’s mystery scene, was only sparely represented in EQMM in Dannay’s day, despite his goal of covering the whole genre. And this may go back to Ronald Knox and his famous “Ten Commandments of Detective Fiction,” published in 1929, number two of which was: “All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.”

A writer of detective stories himself, Knox was an important influence on Britain’s Golden Age of Detective Fiction, and Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee, writing as Ellery Queen, saw the publication of their first novel, The Roman Hat Mystery, in the very year that Knox formulated his commandments for the detective story or “fair play” mystery. Although they gave a distinctly American twist to the Golden Age story, Dannay and Lee were writing very much in the tradition Knox encapsulated—a tradition in which the model for the mystery story was a game (the “grandest game in the world,” according to John Dickson Carr) in which the reader could play along and attempt to solve the crime, given all relevant clues by the author (thus the term “fair play”). When EQMM was sent out into the world more than a decade later, it contained many stories that could not be considered detective stories in Knox’s sense at all—in fact, Raymond Chandler, whose work would eventually appear in EQMM’s pages, formulated his own ten commandments for the detective novel, and they provided a model for a very different type of story. It is worth noting, however, that although Chandler’s commandments nowhere include the word “supernatural,” commandment number three—“It must be realistic in character, setting and atmosphere. It must be about real people in a real world.”—does, in effect, seem to exclude all supernatural elements. So stories involving the supernatural were not considered by either major school of mystery writing—the classical or the hardboiled—to be part of the genre in EQMM’s early years, though for reasons specific to each. By taking a quick look at those reasons, I think we’ll be able to see some ways in which the supernatural tale was able to open doors into the contemporary mystery genre.

For the Golden Age writer, the objection to the introduction of supernatural agency to a detective story was, essentially, that it would be unfair to the reader. For if some force affecting events but operating outside of the laws of nature (or human nature) were to turn out to be at the heart of the puzzle, readers would be unable to solve the problem from clues dropped by the author—they would have nothing to go on, it being impossible to know just what to expect from a supernatural agent. It’s tempting to think, therefore, that a fair-play mystery requires realism, but in fact, I think what’s requried has little to do with realism in the sense in which that term is usually applied to literature. One of the criticisms leveled at writers of the Golden Age school by hardboiled writers was that their stories were artificial constructs, without credible characters or motivation, focusing too exclusively on a complex puzzle. They urged “realism” as an antidote to Golden Age artificiality. What a fair-play puzzle mystery does require, I think, is not realism but a rational framework—a framework in which things take place according to patterns the reader can understand and have a chance to predict, rather than coming entirely out of left field. But I think this need not necessarily exclude the supernatural.

An example that comes to my mind in this regard is the story “Normal” by Donna Andrews, from the May 2011 issue of EQMM, in which the characters almost all have some supernatural powers, but what those powers are, and the limits to them, is made known to the reader early in the tale. So there are rules, and the rules allow for predictability and deduction. I suspect that even Ronald Knox would have considered such a story to be in the Golden Age tradition, even though the characters are supernatural.

But what about the objection to supernatural agency made by the hardboiled school—that a detective story should be about real people in a real world? Many have argued that Chandler’s own beloved character Philip Marlowe is far from “real”—that he is an idealized hero, unrealistic in his incorruptibility. But Chandler felt Marlowe must be so in order for his books to have moral weight, and his objection to the artificiality of the Golden Age mystery was, I suspect, primarily that they treated crime and its solution as a game, rather than striving at the same time to address its moral dimensions. And if that is at the heart of his commandment that the story should be about real people in a real world—that it should relate to genuine and profound moral concerns—I think that stories involving the supernatural need not necessarily be ruled out, for some of the most notable recent examples of such cross-genre mysteries are clearly intended to address moral issues. The several supernatural series of Charlaine Harris (the author who opens our current issue—November/December 2019) seem to me to belong to that category; some of the stories can be seen as allegories, addressing social and moral dilemmas that could not be as easily conveyed to readers using human characters.

For the reasons just mentioned, I think it makes no sense to attempt to exclude the supernatural from our genre—and our genre would be poorer if we did. But there is a reason—and I think a good one—for supernatural tales to remain rather rare and special inclusions for EQMM. We’ve noted that writers can sometimes achieve similar ends to what is achieved with more conventional crime stories using supernatural agency, but surely a tale involving the supernatural is meant to do something in addition to that. It seems to me that it is precisely the “spooky” element—that is, the element of the inexplicable—that attracts readers to such tales and provides the frisson of fear they seek. In a mystery story, what had been inexplicable is generally explained by the end and some moral resolution or at least redemption is attained. But is it not true that in tales of the supernatural, even if the murder itself is solved by rational means, something inexplicable must remain? Some sense of what we cannot fathom—that otherworldly presence? That makes for a different kind of reading experience, and it may draw a different type of audience from the mystery, and so, although there is clearly some crossover between the mystery and the supernatural story (and their respective readerships), the latter will probably never be EQMM’s bread and butter, but instead, a spice.

Happy Halloween to all, and congratulations and good luck to authors and readers enjoying it at the special 50th anniversary Bouchercon, especially our best-short-story nominees: Barb Goffman and Art Taylor for the Anthony and Macavity; Twist Phelan and S. J. Rozan for the Shamus; Craig Faustus Buck for the Macavity—as well as Doug Allyn for winning the Edward D. Hoch Memorial Golden Derringer for Lifetime Achievement and Peter Lovesey for being Bouchercon’s Guest of Honor for Lifetime Achievement!—Janet Hutchings

“What drew you to write crime fiction?”

That’s a question that gets tossed at a lot of crime-fiction writers. It’s a good softball query that usually gets answers such as “Oh, I’ve always loved reading mystery stories, so . . .” or “Nancy Drew” or “I didn’t even know I was writing crime fiction!”

But some crime-fiction scribes answer the question the way I would. They say crime was or had been a part of their lives, and so they had a familiarity with, some might even say a fascination for, things beyond the strictly legal. For me, I grew up around crime. This was mostly because my father—a handsome man who resembled Guy Williams and loved bawdy jokes and afternoon drinks—was a criminal.

That’s a tough sentence to write. It sounds judgmental, negative, a flat label. I never thought of Pop as a criminal and I still don’t. But, by the letter of the law, yeah, he was a lawbreaker.

Oh, nothing crazy, nothing true crime podcast-worthy, like a hitman or bank robber. Sorry if that’s what you were expecting. If it were anything like that, don’t you think I would have done a true crime memoir by now?

No, Pop was a numbers runner.

This was back in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in the ’60s and ’70s. I was a child at the time. My father didn’t live with us. My parents had never married, but they had decided on an arrangement—that Pop would be at our apartment every afternoon while my mother was still at work, so my sister, my brother, and I would not be latchkey kids.

My father would make us lunch—he was a master of grilled-cheese sandwiches—but the kitchen was also his office. There, he’d sip grapefruit juice and gin or have a few beers. We kept a glass for him in the freezer. He had a set chair at the kitchen table, right by the phone, and nearby in the cupboard was a pleather folder with all his papers, paper clips, his fancy metal pen.

And every day, at about two o’clock, the phone would start ringing.

For the uninitiated, the numbers racket is similar to the lottery, just, um, unregulated, therefore, untaxed. To play the game, you call in your three-digit numbers to a bookie, placing bets on each number, indicating whether you wanted to be on the number straight (261) or combination (all the six variations of the numbers 2, 6, and 1, thereby increasing your chance of winning but lowering your winnings).

As a bookie, my father had a set amount of people he called “customers.” He’d take down their numbers and write them into neat columns. His handwriting was neat, confident, efficient. He used onion-thin paper, folded in half with a carbon paper in between. To this day, the scent of carbon paper, of ink always reminds me of my father.

In case you’re interested—and if you’re a crime fiction writer (or reader), I bet you are—the number winner for the day was determined by using the last three digits of the track handle at the local racetrack. The handle is the total amount of money wagered in a day, inevitably a six- or seven-digit number, and this was conveniently printed in the back section of the Daily News.

The numbers ran every day. But on Saturdays, my father took one or all of us for a drive. He drove a black van with no air conditioner and a custom-installed horn that played the theme from The Godfather. La da da di da dum dum dum dum dum.

We thought it was fun to hang out with Pop, because that usually meant getting pizza on Grand Street or hot dogs at the cart next to the BQE. On these drives my father always made stops. Most times he’d tell us to wait in the car, to sit still, and he’d run into buildings for a few minutes and come right back out.

In time I realized that on these stops my father was either picking up money owed him or dropping off winnings. He got a small percentage of anyone’s winnings. and years later he told me that his numbers earnings had gotten him through many hard times.

When I was a bit older, in high school probably, my father took me on one of these drives, and after he came out of one place, he tossed a brick of money on to my lap. He said, “You ever see $10,000 at one time before?”

What do you think my answer was? Exactly. And not since either.

Back then, every once in a while, Pop took us to what he called “the clubhouse,” the headquarters for the local bank. This is where the bookies hung out, dropped off bettings, picked up cash. There were arcade games upstairs, but sometimes we would go downstairs and in the basement there were shelves and shelves of empty cages that Pop told me was once used for cockfighting. At the clubhouse, I got to meet many of my father’s let’s say cohorts, who seemed like regular people to me. Although later I did find out there were men there who would kill people for as little as a six pack.

With all this exposure to crime, it was certain that when I first picked up a typewriter I would turn out . . . it was a horror story about dinosaurs that take over the world, actually. Michael Crichton’s people still owe me a residual check for that. But that was in third grade. Later, in high school, without realizing it, every story I turned in to my creative-writing class was about crime.

And now while I write in genres literary, horror, and speculative fiction, I maintain a special affinity for crime fiction. I don’t mean to romanticize the criminal world, by the way. I understand that laws are laws, and there is an ugly side to all crime. It is just that for me that world is not alien. It is almost comfortable.

What draws any writer to a particular genre anyway? Perhaps many horror writers did see ghosts as children. Perhaps spec fic writers were stung by radioactive scientists. For me, I guess something of my father’s lifestyle, something of that past stuck. Perhaps—not to get too Freudian—crime fiction is my way of maintaining a connection to my father, who while he was a charming rogue, was also distant and hard to know.

Years later, after he had retired to Florida, my father told me that he was still taking numbers and calling them up to a bank in New York. It supplemented his Social Security. And even though doctors had warned him against it, he told me he was still having his drinks every afternoon.