Manju Soni, who writes under the pen name M. J. Soni, is a former eye surgeon turned author. Her debut nonfiction book, Defying Apartheid, captures her experiences as a young activist against apartheid. In recent years, she’s turned to fiction writing. Her short stories have appeared in Akashic Books anthologies, Apeiron Review, The Establishment, and EQMM. Don’t miss her story “Juvenility” in our current issue (November/December 2022)! Manju is a recipient of the Leon B. Burnstein/MWA-NY Scholarship and a 2020 runner up for the Eleanor Taylor Bland Crime Fiction Writers of Color Award. Her recently completed first novel, Precious Girls, is out on submission. She’s an active member of Sisters in Crime and Crime Writers of Color, and for this post she provides reviews of ten new books by crime writers of color that we think will pique your interest. —Janet Hutchings

Stories and storytelling have been part of human culture for as long as there have been humans.

Tales, fables, myths, and legends have been with us for so long we often take them for granted. We rarely ask, who are the storytellers, whose stories are heard, and whose are not, why do some stories become part of our popular culture and others don’t, and the most important question of all, what impact do these choices have on us as the human race.

Through millennia much of storytelling was oral, lessons passed down from one generation to the next, and the next, and the next. But these magnificent waterfalls of human stories all over the world were dealt a terrible blow by colonization. Western Europeans regarded people of color whose lands they conquered, as primitive, as savages. So, they set out to “civilize” these peoples by breaking up families and societies, tearing the bonds between generations and thus severing the continuity of the thread of storytelling that kept people together.

The author Doris Lessing talks of a Shona friend whose grandmother was the storyteller for her clan. But her friend knew not one story of his grandmother’s. “The Jesuits beat all that out of me,” he said. He was flogged, all the children were, for any hint of “backwardness.”

Slavery broke the bonds between the elder storytellers left behind in Africa, and the enslaved people brought to the Americas.

Today, only a few cultures in the world continue this tradition of oral storytelling. Amongst them are the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Australia, widely regarded as the oldest living cultures outside of Africa. They call their stories Dreamings, and they are closely guarded “lessons” told only to a chosen few and repeated back for accuracy, in order to pass on important lessons on geography, on acquiring food and shelter, and of social norms.

In the modern world, the printing press became the main conduit of storytelling which meant only those storytellers with access to it were heard, and this often meant White people.

The publishing industry in the West has struggled to address this issue of systemic racism within it. In the past few years, and especially with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, we have seen a range of authors being published whose stories are as diverse as humans themselves.

Here are 10 exciting crime novels by authors of color that explore worlds often unseen. I hope you find them as fascinating as I did. And you can find more writers of color at the Crime Writers of Color website https://www.crimewritersofcolor.com/books. Founded by Walter Mosley, Kellye Garrett and Gigi Pandian, CWOC is a great resource for both authors and readers.

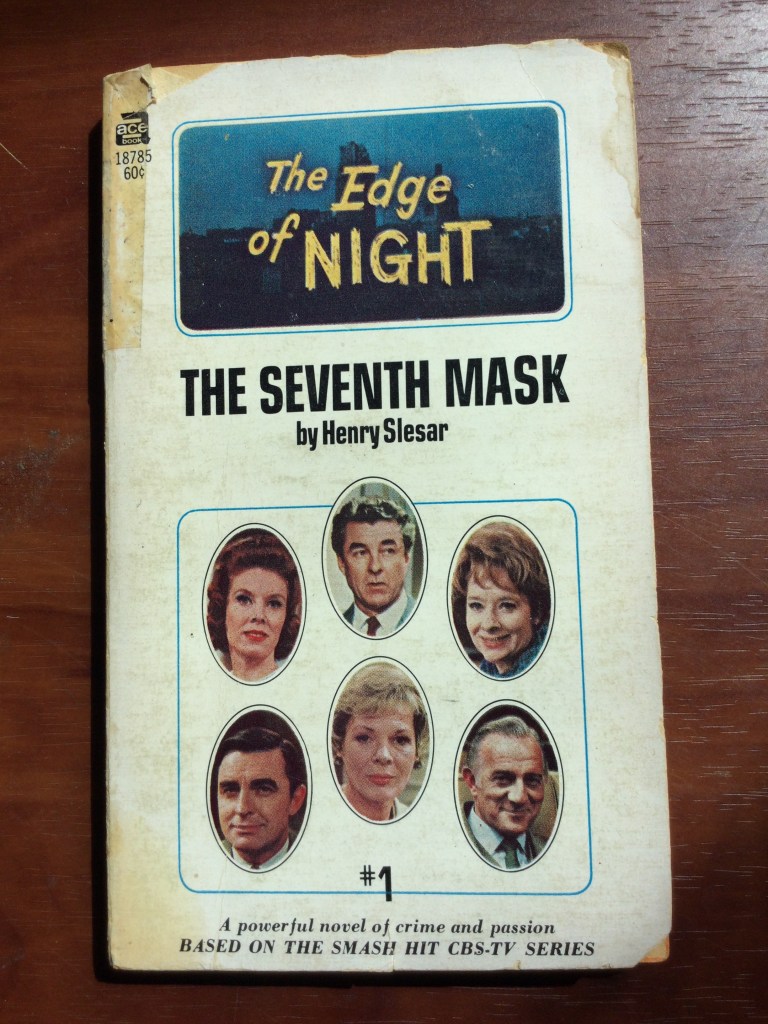

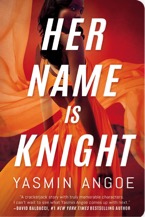

Her Name is Knight by Yasmin Angoe

“Echo cast one more look at herself, making sure the swim cap was securely on her head, the waterproof earpiece embedded in the diamond stud earrings she wore.”

Nena Knight, code name Echo, was trafficked as a child from her village in Ghana. Now, she’s an elite assassin who works for an international agency called the Tribe, a secret organization that ensures Africa’s interests are maintained on the world stage. Interweaving the story of her past with the present, we see Nena become Echo and take vengeance when she learns a new member of the Tribe is the man who murdered her family and sold her into captivity.

Runner (Cass Raines #4) by Tracy Clark

“I yanked the door open and all but flung my half-frozen self into the snug White Castle, the hawk clawing up the back of my neck, my lungs shocked rigid by the subzero wind chill.”

Cass Raines is a PI, and an ex-cop. When the desperate mother of a missing teen comes to her for help, she agrees to help. But the girl doesn’t want to be found, and as Cass digs further she realizes the breadth of the conspiracy that is keeping the girl and other kids on the street rather than at home.

But as Cass gets closer to the truth she and the girl are in an ever increasing danger.

Razorblade Tears by S.A. Cosby

“Ike tried to remember a time when men with badges coming to his door early in the morning brought anything other than heartache and misery, but try as he might, nothing came to mind.”

One of Barack Obama’s Recommended Reads for Summer, Razorblade Tears follows the story of two fathers, one White, one Black, whose gay sons are murdered leaving their baby girl fatherless. We see the men struggle to overcome their own prejudices in order to work together to find the truth and bring the murderers to justice. A poignant portrayal of grief and revenge.

Like a Sister by Kellye Garrett

“I found out my sister was back in New York from Instagram. I found out she’d died from the New York Daily News.”

In a family ravaged by tragedy, loss and the ego of their father, music mogul, Mel Pierce, half-sisters Lena and Desiree, haven’t spoken to each other for years. But when Desiree is found dead, of a suspected overdose, in a park in the Bronx, near the home Lena shares with her aunt, Lena is convinced Desiree was on her way to see her. Why? Did her sister need her?

Lena is a smart and determined protagonist, and like a magician, Garrett unspools the mystery, making everyone a suspect until the twisty end.

Clark and Division by Naomi Hirahara

“Rose was always there, even while I was being born.” Set in 1944, Naomi Hirahara’s story about two sisters, is narrated by Aki, the younger sister, who survives the Japanese internment only to lose her vibrant, beautiful, charming sister to murder in Chicago, on the corner of Clark and Division. It’s a chilling reminder of the impact of historical events on a Japanese-American family and the stoicism required to weather these events.

My Sweet Girl by Amanda Jayatissa

“There’s a special place in hell for incompetent customer service agents, and it’s right between monsters who stick their bare feet up on airplane seats and mansplainers.”

Paloma has lived a privileged life after being adopted from an orphanage in Sri Lanka. Now, at thirty, the man subletting her apartment discovers her secret, and is then found dead in a pool of blood.

On the run, with flashbacks to the harrowing time at the orphanage, we follow Paloma as she runs away from her past but never reaches a safe place.

Arsenic and Adobo by Mia P. Manansala

“My name is Lila Macapagal and my life became a rom-com cliché.”

In this cozy food-themed mystery, Lila, recovering from a bad breakup, moves back home to help her aunt run her restaurant. But when her vindictive ex, a food critic who gives the restaurant a bad review, dies in the restaurant, Lila becomes the main suspect. And so begins a mouth-watering romp to find the real murderer.

All Her Little Secrets by Wanda M. Morris

“The three of us—me, my brother, Sam, and Vera or Miss Vee as everyone in Chillicothe called her—looked like a little trio of vagabonds as we stood in the Greyhound Bus Station, which, in Chillicothe, meant a lean-to bus port in the parking lot of the Piggly Wiggly.”

Ellice Littlejohn is a top-notch lawyer at a firm to match. But when she finds her boss, and lover, shot dead in his office, she walks away, desperate to keep her past from destroying her present. Promoted to replace her boss, she soon realizes everyone has a hidden agenda, and she’s being set up to take the fall. But secrets will out.

Under Lock & Skeleton Key by Gigi Pandian

“Tempest Raj tested the smooth, hardwood floor once more.”

Tempest Raj is a stage magician who has returned home after being accused of a careless and risky magic accident, where she was “apparently” witnessed preparing for the unsafe stunt. She firmly believes her former stage double, Cassidy, was responsible for the accident.

But when Cassidy is found dead inside a wall of a building being constructed by Tempest’s parents’ company, called Secret Staircase Construction, she and her best friend Ivy, have to solve the murder before someone kills Tempest, or accuses her of it.

Diverse and quirky characters, like Tempest’s grandparents, Grandpa Ash who is of Indian ancestry, and Grandma Mor who is Scottish, together with their brilliant fusion recipes, and Tempest’s rabbit, Abracadabra, add a lot of fun in what is an intriguing mystery.

Winter Counts by David Heska Wanbli Weiden

“I leaned back in the seat of my old Ford Pinto, listening to the sounds coming from the Depot, the reservation’s only tavern.”

In 1885, the murder of Chief Spotted Tail of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe resulted in the Major Crimes Act being passed by the federal government. The Act, still in effect today, ensures that a serious felony committed on a reservation by a Native person has to be referred to the FBI, but the FBI has a right to decline prosecuting if they deem fit. The result is many victims and their families are left without justice, in the gray area between the FBI and tribal police. This is when they turn to Virgil Wounded Horse, the protagonist of Winter Counts. A local enforcer on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, Virgil is also a vigilante. Following the trail of a new drug cartel rapidly expanding its heroin dealings on the reservation, Virgil has to follow the trail to Denver. And things become personal when his nephew is caught in the crossfire.