Our blog post this week is by Russell Atwood, a former managing editor of EQMM whose first work of fiction appeared in EQMM’s Department of First Stories. He went on to write two novels starring P.I. Payton Sherwood and, most recently, the haunted-house novel Apartment Five Is Alive. The latter is perfect for this Halloween season and it’s now available as an audiobook narrated by Jack de Golia, available on iTunes and Audible.com. Bram Stoker Award-winning author Tom Deady says the book is “Full of compelling characters and genuinely creepy scenes . . . The climax is claustrophobic and ultimately stunning.” Russell is also the creator and writer of the comedy-horror-puppetshow The Bride of Pugsley on YouTube channel SidMartyLovecraft. His subject for this post is a writer whose work he would have come across often during his years at EQMM, the unforgettable Henry Slesar. —Janet Hutchings

One of the drives central to all writers is immortality. Whether they acknowledge it or not, at some point all writers look around and notice “Life is short” and many stories go untold and lives are forever forgotten. All writers attempt to create something that will weather through all ages, long after their passing. Henry Slesar can rest easy that he’s come closer than most.

Prolific in numerous fields of writing—sci-fi, pulp fiction, daytime soap operas, advertising copywriting, television and movie screenwriting, award-winning mystery novels—author Henry Slesar was born June 12, 1927 “Henry Schlosser” in Brooklyn, NY, his parents Jewish immigrants from Ukraine. He attended the School of Industrial Arts in Manhattan and soon found he had a knack for copywriting and design. At the age of 17 (right after his graduation), Slesar was hired by the NY advertising agency Young & Rubicam, launching his twenty-year career as an ad man in the era of Mad Men. He is credited for coining the term “coffee break” and a long-forgotten but hugely successful “The Man in the Chair” ad campaign for McGraw-Hill.

He published his first short story, “The Brat,” in 1955, in Imaginative Tales magazine. The 1950s saw an explosion of activity for Slesar, setting a pace he maintained throughout his career, turning out clean, quality prose in a variety of genres and mediums, though suspense was always his forte. In 1957 alone, Slesar published over forty short stories under his own name and various pseudonyms such as O. H. Leslie (the O.H. presumably a nod to author O. Henry, because many of Slesar’s stories climaxed in a twist ending). In 1960, he wrote his first original novel, The Gray Flannel Shroud, a mystery set in a big advertising agency (which the author had ample first-hand experience to draw from) where a murder is committed while the staff is in the middle of promoting a new baby food. It won the Edgar Award for Best First Mystery Novel from the Mystery Writers of America.

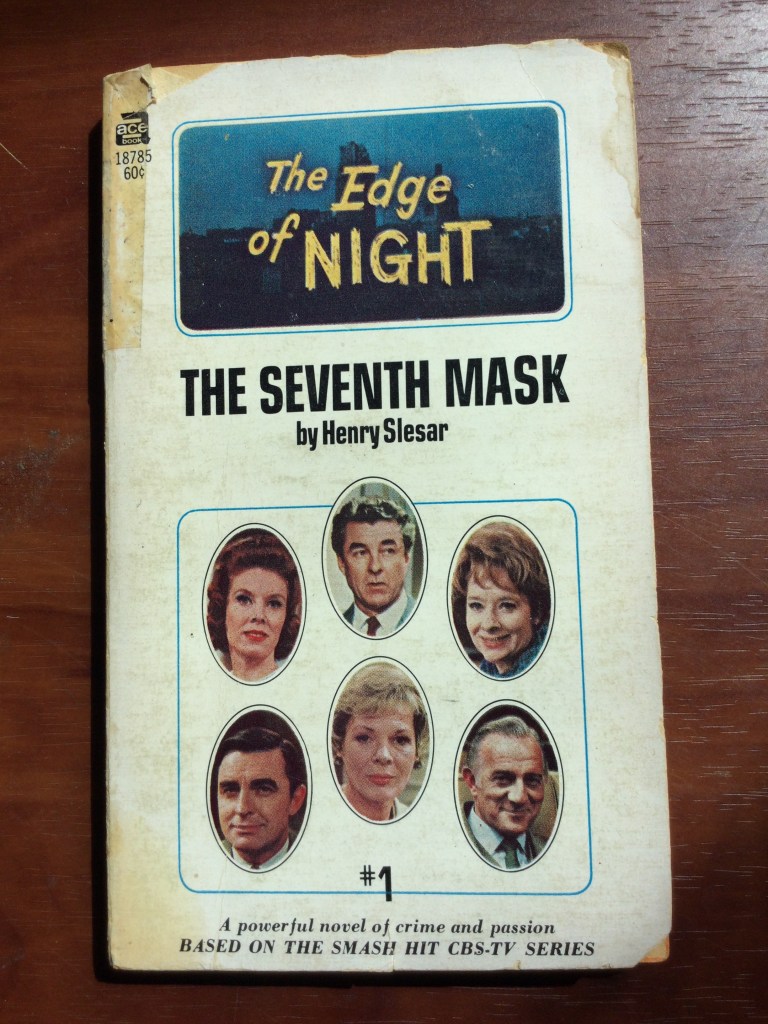

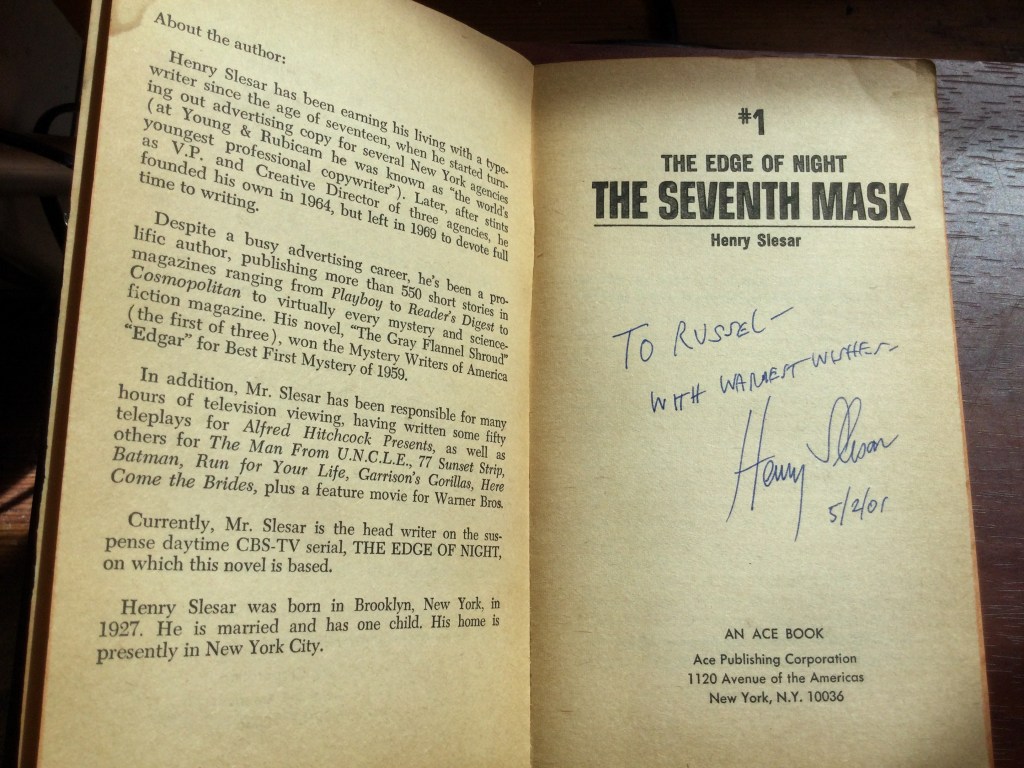

It was also around this time that Slesar opened his own advertising agency and began writing for television, igniting an extraordinarily long relationship with the CBS daytime soap opera The Edge of Night. In The Soap Opera Encyclopedia, writer Chris Schermerin comments that “Slesar proved a master of the serial format, creating a series of bizarre, intricate plots of offbeat characters.” He eventually became the head writer for this mystery-oriented serial from 1968 to 1980, leading TV Guide magazine to once refer to him as “The Writer with the Biggest Audience in America.” He won an Emmy in 1974 for his writing on the show, wrote an original novel based on the series (The Seventh Mask), and garnered numerous nominations and nods from the Writers Guild, and a second Edgar for best television script in 1977. He also wrote for other daytime and late-night serials such as One Life to Live, Somerset, Executive Suite, and Capitol. (Later, in 1998, Slesar would draw from his experience to write the mystery novel Murder at Heartbreak Hospital, about murders committed on the set of a daytime soap opera).

In 1960, director Alfred Hitchcock came across one of Slesar’s short stories, “M is for the Many,” in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and acquired it for an episode of his television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, retitling it “Heart of Gold.” This began a relationship between the two that led to twenty-one of Slesar’s tales being adapted for the show.

In the introduction to his short story collection Death on Television, Slesar wrote about where he and Hitchcock met creatively in relation to their love of the “twist ending”:

“For some people, irony may seem like a by-product of cynicism. Anatole France called it ‘the last phase of disillusion.’ But for Hitchcock . . . irony was the key ingredient of storytelling, along with its two components: humor and pity. “Let’s face it. There’s nothing intrinsically funny about crime…[Hitchock] made a conscious decision to put the story before the gory. He chose delight over fright.

“It wasn’t merely a cynical outlook on life that dictated the Hitchcock choices. It was an attitude that smiled, sometimes sadly, upon the frailties of the human personality. It was more than just a ‘sense of humor.’ The taste for irony, in the words of Jessamyn West, ‘has kept more hearts from breaking than a sense of humor—for it takes irony to appreciate the joke which is on oneself.’“

Slesar was a master of the twist ending, and often these types of stories are labeled gimmicky, but Slesar’s twists always grew out of the foibles of human beings.

In the 1970s, several of these stories were also used in the attempted rebirth of radio drama on American radio when Himan Brown (the creator of the old-time-radio show Inner Sanctum) started the CBS Radio Mystery Theatre. Brown chose one of Slesar’s stories, “The Old Ones Are Hard to Kill,” to launch the new series and during the decade-long run forty-three short stories of his were transmitted over the airwaves.

In 2001, I ran into Henry Slesar at a mystery writers reading in the East Village, and I told him how now over this new thing called “the Internet” I was able to listen to all the old broadcasts of CBSRMT. He chuckled and said, “Himan would be happy.” But I don’t think he quite believed me. And as fertile as his imagination was, I don’t think he could have imagined that today you could also watch old episodes of his series The Edge of Night, the tapes of which he thought were lost forever. But it turns out old fans recorded these shows on their VCRs while they were at work and now they are making them available to a whole new generation via the platform of YouTube.

This Halloween season I want to focus on five of Slesar’s stories that appeared on CBS Radio Mystery Theatre. They are guaranteed to leave you with a chill down your spine:

1) “Prisoner of the Machines” (01/16/1980), starring a young John Lithgow. A sci-fi tale that starts off with a classic premise and wrings every last futuristic nightmare out of it.

2) “Kitty” (04/09/1980) Suffer from Ailurophobia? The morbid fear of cats? Then you might want to pass on this horror story of an Egyptian mummified cat-queen living in 1970s Manhattan. It leaves marks.

3) “Murder Museum” (04/09/1974) A wax museum is the setting for a tale of a young artist tormented by his tragic family past, which becomes the newest exhibit in the Chamber of Horrors.

4) “Bargain in Blood” (06/10/1974) This creepy, fantastic tale might be familiar as it was filmed as an episode of the original Twilight Zone, about a young man who discovers he can “swap” anything his heart desires. But buyer (and seller) beware.

5)” The Last Escape” (10/17/1974) This story was filmed as an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents and is about a second-rate escape artist and third-rate human being who decides to make a comeback recreating one of Houdini’s greatest escapes. But his downtrodden wife and assistant has an escape of her own in mind. This is to me a classic Slesar story, because break it down to simple facts and it would make a gory and dismal newspaper story, but in Slesar’s hands the shocking ending is a delight.

These radio shows can be listened to on numerous sites including YouTube, archive.org, and for great details on this whole series check out the CBS Radio Mystery Theatre page: CBSRMT.com

The advent of the Internet has given new life to these broadcasts, introducing them to a new generation of listeners, and for the writers maybe even a slice of immortality.

Henry Slesar died April 2, 2002 at the age of 74, but he is immortal.

When I was a kid I would sometimes sit with my grandmother as she watched “my stories.” I was an adult before I realized that the reason the only one i enjoyed was The Edge of Night was that it was based in mystery, not romance. Slesar was a great short storyist.

My Husband and I have been watching a lot of classic TV, including plenty of Hitchcock, and we always take note of a Slesar story! First-rate! And I have plenty of the stories in the old Alfred Hitchcock anthologies and in a couple of his hard-to-find collections!

The Edge of Night episodes on YouTube are not from the Slesar period. These are exclusively the ABC network shows produced after Slesar’s departure, the same ones syndicated and shown on USA many years ago.