In recent years writer, editor, and translator Josh Pachter, whose career in mystery fiction began with a story in EQMM when he was still in high school, added another role in which he contributes to our field: organizer of mystery events—something he talks about in this post. Josh manages to keep writing fiction in the midst of all his other mystery-related activities. He has a new story, “Texas Kinda Attitude,” in our current issue, May/June 2024, and his first novel, Dutch Threat, appeared in 2023 to stellar reviews and nominations for the Lefty and Agatha Awards. Hats off to one of our genre’s most versatile contributors. —Janet Hutchings

“Noir at the Bar” is a concept that, like Topsy, has growed and growed.

It began in Philadelphia in 2008, organized and hosted by Peter Rozovsky. “I like to tell people I am the father of Noir at the Bar,” he says, “but the sort of father who did not always pay child support.” Rozovsky’s first events featured only one author each and consisted of a reading followed by a Q&A. Jed Ayres and Scott Phillips soon brought N@tB to St. Louis, adding multiple writers and cutting the Q&A, and the concept spread to New York, Los Angeles, and eventually many other cities in and not in the U.S.

My own first exposure to Noir at the Bar came in 2015, when I attended one of author Ed Aymar’s events at the Wonderland Ballroom in Washington, D.C. Two years later, in October 2017, I read my story “Selfie” (which originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of EQMM) at another of Ed’s Noirs and was gratified to be voted the audience’s favorite, for which I was presented with an engraved sword I felt very nervous carrying home on the Metro.

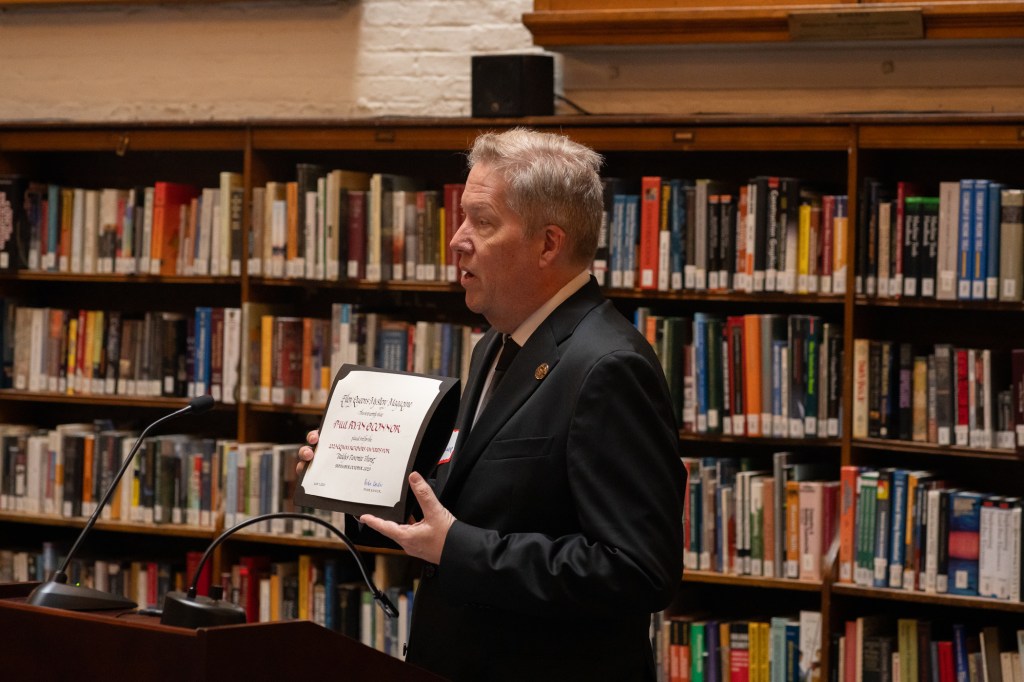

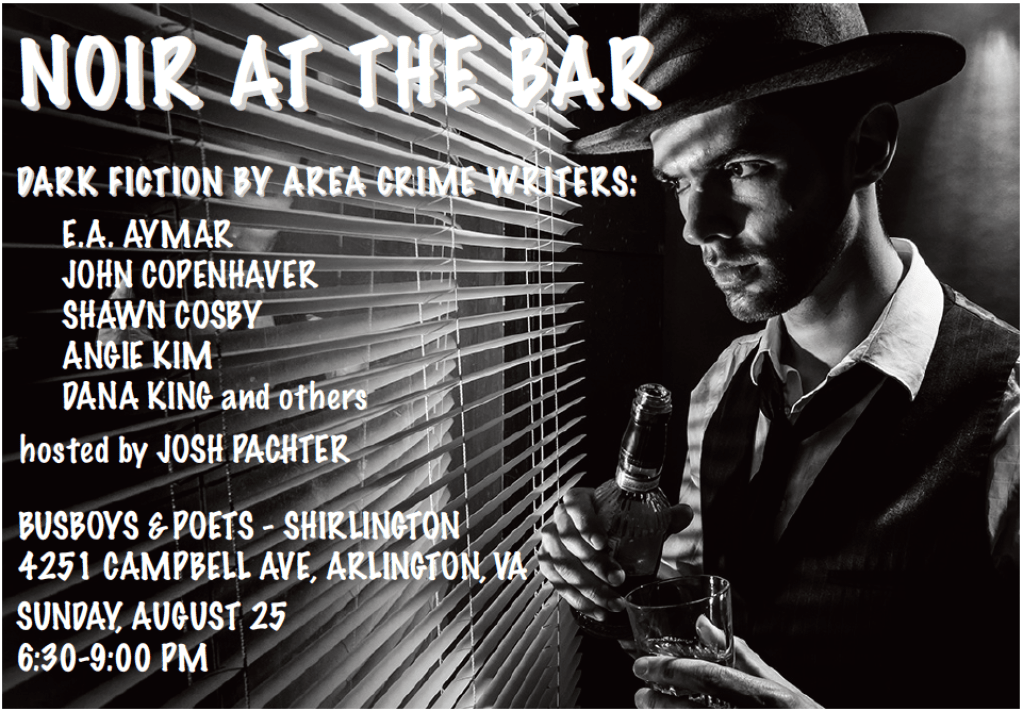

In 2019, I asked Ed if he’d mind my putting together a Northern Virginia edition of Noir at the Bar. He told me that he didn’t own the concept—in fact, no one owned the concept—so I should feel free to go ahead. The Shirlington (VA) Busboys & Poets—a combination bar, restaurant, and bookstore—agreed to provide us with a venue, and on August 25 a gratifyingly large crowd gathered to hear readings by Ed, John Copenhaver, regular EQMM contributor David Dean, Angie Kim, Jehane Sharah (who’d recently been featured in EQMM’s “Department of First Stories”), and Stacy Woodson (who’d just won EQMM’s Reader Award for 2018). Our pre-event promotion listed Shawn Cosby and Dana King as also reading, but Shawn wound up unable to attend and Dana was feeling ill and unfortunately had to leave before his turn to read.

Every N@tB host does things differently. Ed Aymar, for example, allows “his” readers to read either complete short stories or excerpts from longer works, and in the early days of his hosting he awarded a prize (such as my sword) to each event’s audience favorite. I decided to restrict “my” readers to reading complete short stories, and instead of giving one prize to one reader I gave every member of the audience a free raffle ticket and, after each reading, have the reader pull a number from a hat so I can give prizes to multiple lucky attendees. Each reader contributes a book or magazine to be used as a raffle prize, EQMM and AHMM chip in copies of their latest issues, and several publishers I’ve worked with (Down and Out Books, Crippen & Landru, Untreed Reads, Genius Book Publishing, Misti Media, Destination Murders) have also donated prizes.

In November 2019, I did a “Special Ho-Ho-Homicide for the Holidays!” edition of Noir at the Bar, and in February 2020 a “Special Hearts and Daggers!” edition, both at Busboys & Poets, whose management was happy to continue to host us, since most of our attendees and readers ordered dinner and drinks before and during our events and tipped their servers generously.

I scheduled a fourth Northern Virginia N@tB for June 2020, but COVID put the kibosh on that plan … and I probably would have had to cancel it, anyway, since my wife Laurie and I moved down to Richmond at the beginning of the pandemic.

Actually, our new house is in Midlothian, a suburb about twenty minutes west of Richmond—more specifically in Brandermill, a lovely 1970s planned community ringed around the southern and western shores of the Swift Creek Reservoir.

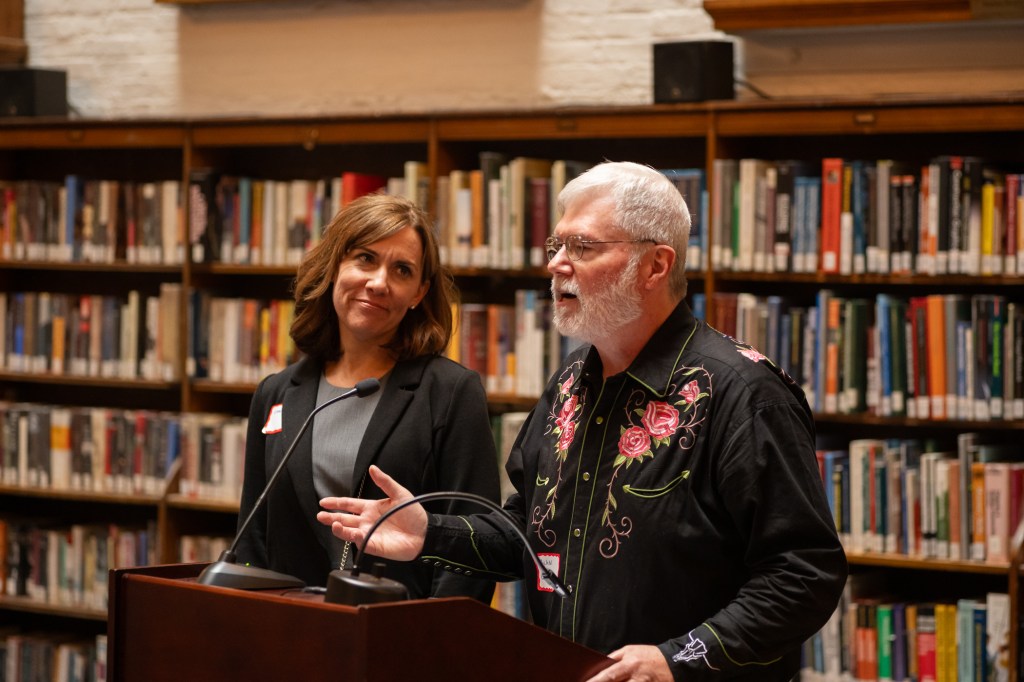

Brandermill is also home to a restaurant, the Boathouse at Sunday Park, which overlooks the water, and I think it was Laurie who first suggested that it would be a perfect venue to host a “Noir at the ’Voir” series. I loved the pun, wished I’d thought of it myself, and when it began to be safe to gather in public again I met with Anne Roy, the Boathouse’s events manager, who agreed to let us use their Swift Creek Room for free.

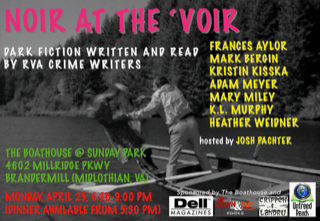

We held our first Noir at the ’Voir at the end of April 2022, with readings by local authors Frances Aylor, Kristin Kisska, Mary Miley, K.L. Murphy, and Heather Weidner, plus Mark Bergin and Adam Meyer from Northern Virginia. It was a hit—we came very close to filling the sixty-some seats in the Swift Creek Room—and the Boathouse invited us to come back quarterly. Our July event was again a mix of local and Northern Virginia readers, and we added the Lifelong Learning Institute in Chesterfield to our list of co-sponsors. (LLI loaned us a speaker and microphone and donated two gift certificates, each good for a semester of free courses.)

Our October 2023 Noir was different in a couple of ways. First, we cut the number of readers from eight to six, partly so that we could wrap things up a little earlier in the evening but mostly because there aren’t nearly as many crime writers in the Richmond area as there are in Northern Virginia, and I didn’t want to ask people who’d already had a chance to read to come back and read again. Second, this was the first time I didn’t host my own Noir: from September through December of 2022, I was teaching two courses in short crime fiction at the University of Ghent in Belgium (see “Passport to Crime Fiction” in the 12/08/22 edition of Something Is Going to Happen), so I was almost four thousand miles from Richmond on the night of the event. My wife volunteered to take over the hosting duties for me, and by all accounts acquitted herself admirably. (Thanks, Laurie!)

I was back on duty for the February 2023 event, for which my daughter, Rebecca K. Jones, flew in from Arizona to read. (Becca has had two courtroom novels and several short stories published. One of the stories, “History on the Bedroom Wall,” was in EQMM’s September/October 2009 issue; we wrote it collaboratively, and its placement made me the only person who’s ever appeared twice in the “Department of First Stories”!)

After three more quarterly Noirs (May, August, and November 2023), I regretfully acknowledged that I was just about out of first-time readers. So I skipped an early-2024 event and scheduled one final Noir at the ’Voir for May 7, 2024. For that one, regular EQMM contributor (and three-time Readers Award winner) David Dean drove down from New Jersey, John DeDakis (author of the Lark Chadwick series) came from Baltimore, and Matt Iden (author of the Marty Singer mysteries) and Kristopher Zgorski (who writes EQMM’s BlogBytes column and with his collaborator Dru Ann Love just won the Agatha Award for Best Short Story for “Ticket to Ride,” from my Happiness Is a Warm Gun: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Songs of the Beatles anthology) came from Northern Virginia. The other two readers—K.L. Murphy (author of the Detective Cancini series) and LynDee Walker (author of the Nichelle Clarke and Faith McClellan series) live close by in the Richmond suburbs.

A couple of noteworthy things happened at this final ’Voir. Although Kristopher Zgorski wrote a new story especially for the event, he didn’t feel comfortable reading it himself, so he introduced it and his husband, Michael Mueller, read it. And Kellie Murphy, who’d read at the first Noir at the ’Voir, circled back around and read a different story at this last one. Once again, the event was a success. The stories were excellent, the readings were smooth and compelling, the winners of our prize packages (which as usual included copies of both EQMM and AHMM) were delighted to receive them, and several of the regular attendees told me afterward that this was the best Noir at the ’Voir yet.

I have mixed feelings about bringing the series to a close. I’ve enjoyed putting the events together and hosting them, and it’s been a pleasure giving dozens of crime writers the opportunity to read their stories to appreciative audiences. But now it feels like time to move on. I’m not saying that I’ll never host a Noir event again—but I think the series overlooking the beautiful Swift Creek Reservoir may well have run its course. Unless, of course, some new crime writers move into the Richmond area, or some people who already live here start writing crime fiction. If either or both of those things happen, well, who knows?!