Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet have been writing together for more than forty-five years. Together, as Hal Charles, they are the authors of more than 200 short stories, one of which is “Nothing Good Happens After Midnight,” in our current issue. Here, they talk about breaking into the mystery-writing market and the influence of our magazine’s founding, eponymous editor.—Janet Hutchings

In the late 1970s, the two of us were struggling mystery writers who still subscribed to many mystery magazines as well as Erskine Caldwell’s pronouncement that “Publication of early work is what a writer needs most in life.” And a little cash for our prose efforts wouldn’t have hurt. After receiving five or ten dollars for a story from Skullduggery and Black Cat Mystery Magazine, we realized the truth that “Crime writing doesn’t pay . . . enough.” Desperate to break into the higher-paying markets like EQMM, we couldn’t figure out how.

As teachers of literature and creative writing, we knew we wrote well, and we had long passed the so-called Hemingway Limit of first writing a million words. Taking our cue from the first writer of detective stories, Edgar Allan Poe, we decided to try his approach to getting published as demonstrated in his famous parodic essay “How to Write a Blackwood Article” (Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine was famous for its tales of sensation).

Poe’s effort is actually an excellent example of the market analysis, a technique we taught our creative-writing classes. Like its business counterpart, literary market analysis examines character, plot, method of narration, and theme in detail. We decided to examine EQMM and found in the year of our study, for instance, that though 80% of the magazine’s readers were feminine, 85% of the stories’ major characters were male, and 10% were private investigators (as an aside, these figures are time-specific and no longer accurate).

We wrote up our study in a Poesque parodic manner, and under the title of “Ask Mr. Mystery,” we submitted it as a presentation at an annual conference held in Sarasota to honor John D. MacDonald. The presentation was accepted, and afterward two people talked to us. One was Mike Nevins, a frequent contributor to EQMM, whom we had met previously at a pop-culture convention in St. Louis. Mike encouraged us to submit “Ask Mr. Mystery” to the editor at EQMM, Fred Dannay. John D. MacDonald chimed in, agreeing with Mike’s direction (aside #2: “Ask Mr. Mystery” was subsequently published in JDM Bibliophile27 [January 1981, pp. 12-15]).

Should we send it to Mr. Dannay? One of our guiding lights was a quote we saw attributed to Robert Frost (aside #3: when the Internet occurred, we could never substantiate the claim): “It’s hard to hate someone up close.” Once, while attending a conference in Nashville, we walked to the office of a popular magazine, and interestingly, because it was the lunch hour, the editor was the only one there. He talked to us for an hour about the type of fiction he was looking for, invited us to submit, and helped us sell several stories to his publication.

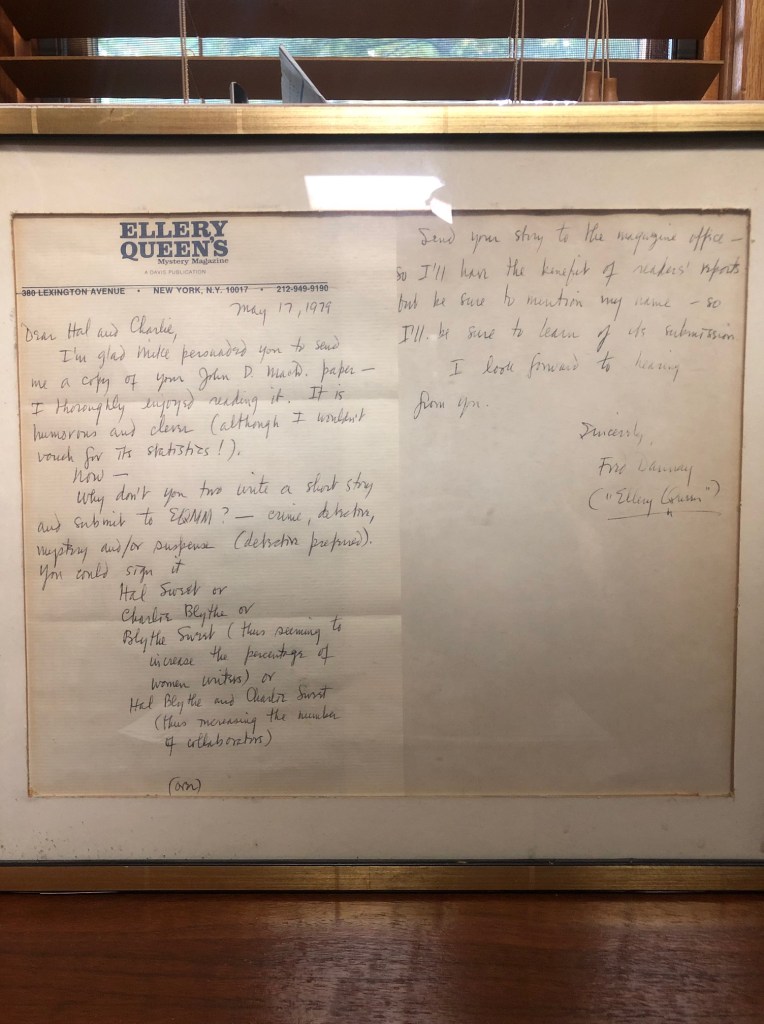

So we sent “Ask Mr. Mystery” to Fred Dannay, not expecting much but realizing we had nothing to lose but our poverty. Unbelievably, we received a letter from Fred that we framed and hung in our offices for 39 years:

- May 17, 1979

- Dear Hal and Charlie,

- I’m glad Mike persuaded you to send

- me a copy of your John D. MacD. paper—

- I thoroughly enjoyed reading it. It is

- humorous and clever (although I wouldn’t

- vouch for the statistics!).

- Now—

- Why don’t you two write a short story

- and submit it to EQMM?—crime, detective,

- mystery and/or suspense (detective preferred).

- You could sign it

- Hal Sweet or

- Charlie Blythe or

- Blythe Sweet (thus seeming to

- increase the percentage of

- women writers) or

- Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet

- (thus increasing the number

- Of collaboration).

- Send your story to the magazine office—

- so I’ll have the benefit of readers’ reports—

- but be sure to mention my name—so

- I’ll be sure to learn of its submission.

- I look forward to hearing

- from you.

- Sincerely,

- Fred Dannay

- (“Ellery Queen”)

Previously, we had been used to receiving with our stories (and letters to editors) simple, small, white rejection slips that all played on the theme of “This does not suit our needs.” We received so many we actually started papering our office walls with them, so you can imagine our surprise at opening an envelope from EQMM with an actual letter. Moreover, the letter wasn’t from some anonymous slush-pile reader, but the editor-in-chief of the magazine himself, Fred Dannay.

Look at all the actual aid he provided:

- – Psychological encouragement for us to persist

- – Praise for our article (though with his usual humor he added he wouldn’t “vouch for the statistics”)

- – An RSVP invitation to submit a mystery story

- – A clue to a successful EQMM tale “detective preferred”

- – The range of stories EQMM favors: “crime, detection, mystery and/or suspense”

- – Advice on a nom de plume. Clearly Fred was showing that the industry preferred one writer rather than a team, so drawing on his own experience with Manny Lee, he suggested various reductive names that would imply a single author (Hal Sweet, Charlie Blythe, Blythe Sweet). Ultimately, we used his advice to come up with Hal Charles.

- – The mechanics for increasing the chances for a successful submission (“send your story to the magazine office,” “be sure to mention my name”)

- – Final encouragement (“I look forward to hearing from you”).

In seven years of “collabowriting,” we had performed market analysis, read and taught hundreds of mysteries, and submitted dozens of stories, but we had never received such help. Of course, we took Fred’s advice and set to work on crafting a new mystery tailored to EQMM’s specs. That product, “Sudden Death,” was submitted, revised by Fred Dannay himself, and finally appeared in EQMM’s Department of First Stories, its 547th “first story” the blurb on p. 75 of the April 7, 1980 issue noted. The prestory blurb also labeled our effort “a dying-message story (oh, Ellery, what hath thou wrought?).”

As Fred/Ellery had suggested to us, “Sudden Death” focused on a detective sports agent trying to fathom the significance of the dying clue BLITZ left by a dying quarterback. The mystery followed the familiar pattern of showing how the dying clue might point to a number of suspects, but in the end indicated only one. And the story was submitted under our combo-pseudonym, Hal Charles.

The blurb also iterated another mystery, one we never solved. According to the editorial blurb, our “first submission to EQMM was the most unusual we have ever received. The story was acted out as a drama and sent to us on a cassette.” Here’s the problem. We had sent Fred a paper version of our MacDonald conference presentation, not a taped version. We always guessed it was either John D. himself or, more likely, old friend Mike Nevins who had gone to the trouble to help us (aside #4: Mike offered to read several of our early mysteries and provided excellent critiques of our fiction).

Our next EQMM publication was “The Talk-Show Murder” (July 23, 1980), then ”Human Interest Angle” (December 1, 1980), which was followed by a Sherlock Holmes pastiche, “The Adventure of the Hare Apparent” (January 1981).

“Sudden Death” provided us with an important springboard. From that point on, whenever we submitted a mystery, we always pointed out in paragraph two that key credential: we had published in “The World’s Leading Mystery Magazine” (to quote EQMM’s masthead).

One publication in particular started accepting a lot of our stories, Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine. At first we received encouraging notes on rejections from then assistant editor Chuck Fritch, but when we started following his advice, our stories were accepted. Once we mailed him five manuscripts in a single envelope, and Chuck took three of the stories. And when the previous Brett Halliday ghost writer (Davis Dresser had long since stopped writing Shayne) stepped down to cowrite romances with his wife, we were offered the chief ghost position. At first Chuck demanded we send him outlines of our stories for pre-approval. No sooner did he begin to trust our ability so that outlines were no longer de rigeur than Chuck had a new condition. He sent us Polaroids of covers commissioned for the Girl from U.N.C.L.E. magazine but not used, and we were supposed to write stories and submit them with the appropriate cover photo. Unfortunately, Noel Harrison, the girl from U.N.C.L.E.’s partner, was blond and Mike Shayne was always “the raw-boned redhead,” but no one seemed to care about this discrepancy.

Over the years as its editors changed, we have continued to publish in EQMM, but usually in spurts when we are not doing novels. Around the turn of the century, we published with Janet Hutching’s expert guidance (she literally had us cut “Ghost Cat” in half) some of our more literary mysteries—“Sharper Than a Serpent’s Tooth” (June 1999), “Slave Wall” (July 2000), “Moody’s Blues” (November 2002), “Draw Play” (May 2003), and “The Death of Doc Virgo” (September/October 2004). Then, after writing ten novels in our Clement County Saga, we returned to our own paracosm, Clement County, with “Ghost Cat” (March/April 2020), “Nothing Good Happens after Midnight” (May/June 2021), “The Reawakening” (TBA), and “Sound Moral Character” (TBA).

If it weren’t for the gracious intervention of Fred Dannay, our writing would probably have been mostly marked by academic books and articles—in other words, oblivion.