A writer who grew up in Mumbai, India and currently lives in suburban Virginia, Smita Harish Jain has had a number of crime short stories published, including one in the recent MWA anthology, When a Stranger Comes to Town. Her first story for EQMM, “The Fraud of Dionysus,” appears in our current issue (July/August 2021), and if that whets your appetite for more of her work, don’t miss her stories in Malice Domestic’s Mystery Most Diabolical or the next volumes from the Chesapeake and Central Virginia chapters of Sisters in Crime. In this post, she talks about the process of finding her voice in fiction. —Janet Hutchings

“Art makes the familiar strange so that it can be freshly perceived. To do this it presents its material in unexpected, even outlandish ways: the shock of the new.”

The first time I heard this Viktor Shklovsky quote, I was sitting, not in an art class, but in a sociology class in college. The professor was telling us about Margaret Mead’s landmark work, Coming of Age in Samoa, to show us both the application of this quote and its evolution into its more commonly known variation, “Make the familiar strange and the strange familiar.”

For her research, Mead traveled to Samoa to study adolescent girls and their attitudes about sexuality. She compared their experiences with those of their counterparts in the United States and found that the female adolescent experience in Samoa was a far cry from the anxious and confusing time girls in the United States faced. Teenage girls on the island nation engaged in socially sanctioned casual sex, which both reduced the incidences of rape and increased the ease with which they faced sexual encounters as adults. In making the familiar strange, Mead changed the way people thought about female sexuality and urged a reconsideration of the American female’s sexual upbringing, as well as of how sex education was taught in schools. Her seminal work on the subject made Mead one of the most respected anthropologists in the country.

Years later, Shklovsky’s words came up again, this time in a graduate school management class, in which the professor used Henry Ford’s much-lauded assembly-line method for car manufacturing, to demonstrate the other facet of this quote, make the strange familiar.

During a tour of a meat-packing facility, Ford was struck by the idea that workers did not have to move around the warehouse to do their jobs. Instead, large slabs of beef and pork were brought to them on overhead conveyor belts, and each worker cut a part of the animal for processing and packaging. Ford saw the possibilities for auto manufacturing and adopted a similar system in his own plants. His workers no longer dragged bins filled with tools and car parts from car to car, adding their part to the work in progress. Instead, Ford brought each car under construction to them, on an assembly line, forever revolutionizing the way cars are made – adding specialization, increasing efficiency, and lowering costs – as manufacturers the world over copied his process.

The third time I came across this quote was when I was working on my first novel, a suburban mystery set in Rockville, Maryland. When it was done, I was convinced that I had written a winner. After all, it had everything a cozy mystery required: an amateur sleuth, a small community, and no violence on stage. It had twists, humor, and content everyone would be familiar with. So pleased was I with the finished product that, for the first time ever, I shared my writing with someone else—an avid reader, who knew a good story when she read it.

I sent her the manuscript, and we arranged to meet the following week to discuss it. While I waited, I thought often about one of my favorite New Yorker cartoons, the one where the man hands his wife his manuscript and says, “Here it is—my novel. I’ll be interested to hear your compliments.”

Suffice it to say, I heard few compliments. Of course, she was kind, knowing it was my first time showing my writing to anyone, and said all the encouraging things a friend says. It was clear, though, that she was building up to a big “but.”

“Where are you in this story?” she finally asked.

I knew she didn’t mean for me to write a story starring me. What she meant was, “Whose voice is this?” I had decided that in order to keep readers interested, I would have to write about the things they knew, not the things that were part of my experience, even though this was where my voice was strongest. As a result, the story was flat and dull.

The next thing of mine that she read was a short story – my first published work – about superstition and cosmic justice, set in Mumbai, India, where I grew up.

“There it is,” she said. “There’s your voice! Why don’t you write more stories like this one?”

I thought, but didn’t say, that I didn’t think most readers would understand my references, since they didn’t live them, and that I couldn’t possibly make them relatable.

She persisted, and I relented, and the writing became easier. The next several short stories I wrote were based on my childhood in India, my life as an academic, my experience as an immigrant, my hobbies, my interests, my passions. Not all of them, but enough of them to see a difference in my ability to tell a story and to enjoy telling it. With each new work, I tried to make my familiar my readers’ familiar; to find an element of truth, maybe even universality, in my uncommon events, set in unusual places, about unknown people, and make them about anyone.

I’ve written about dowry deaths and ritual castrations, honor killings and snake charmers. I’ve also written about astrology and wine and the small Virginia city in which I live. So, what is familiar about castration to the “any reader”—a sense of community and belonging; dowry deaths—greed and climbing the social ladder; snake charmers—a need to believe in magic. It’s not about writing what you know or writing what the market demands. It’s about finding the common threads that connect all of us and weaving a story out of them.

I am a relative newcomer to mystery writing, so my view is still a bit from the outside looking in. The biggest lesson I’ve learned, however, is my stories can be many people’s stories, if I look beyond the surface happenings to the core elements. Readers want to see themselves in what they read, and if they can see a similarity in people completely new and different from them, so much the better. For me and my writing, the quote had morphed yet again, this time to “make the familiar [to me] familiar [to them].”

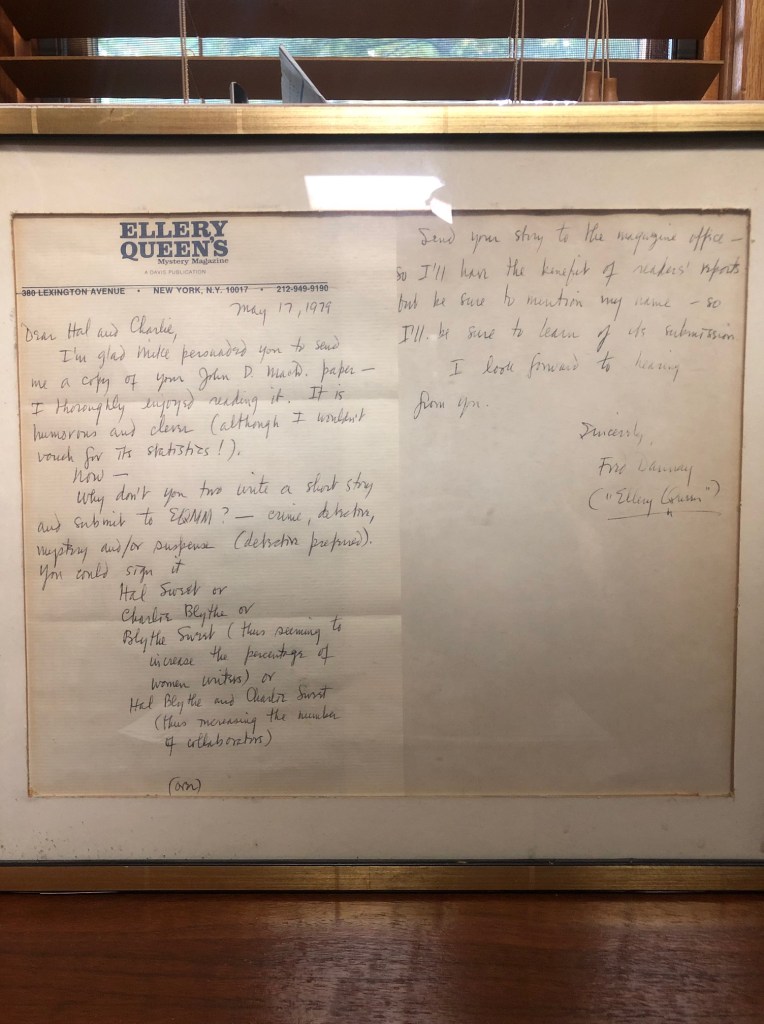

That Rockville suburban mystery is permanently relegated to the bottom of a deep drawer, likely never to see the light of day again. As for my story in the current Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine (July/August), a story involving a lot of wine drinking, my friend never asked me, “Where are you in this?”