This is the first post for our site by Maxim Jakubowski, but he’s someone whose name is known to nearly everyone in the mystery field. He worked for many years in publishing and later owned London’s Murder One bookstore for twenty years. His first novel was published when he was sixteen and he is now the author of twenty-one novels spanning several popular-fiction genres. He’s a well-known anthologist and short story writer as well, and he’s currently the chair of the U.K. Crime Writers’ Association. His latest novel is The Piper’s Dance (2021), and he’s compiled two anthologies we’ll be watching for next year: The Perfect Crime, a landmark anthology of material from writers of color, co-edited with Vaseem Khan, and Black Is the Night a collection of new stories inspired by Cornell Woolrich. In this post he talks about his lifelong love for fiction magazines such as EQMM and his passion for collecting.—Janet Hutchings

It’s no secret that I began my life in the world of books in the SF and fantasy genre—initially as a reader, then as fanzine editor—and quickly graduated to actually writing fiction. But when I look back, I have come to the realization that I owe it all to magazines.

I must have been just about fourteen, and living in Paris, France, where my father had set up business just a couple of years following my birth in London, and had become an avid borrower at our local bibliothèque using my mother’s library card, indulging at the rate of almost a book a day in fiction galore, whether Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, SF, or crime and mystery (Agatha Christie in French translation, Arsène Lupin, Fantomas, but also early Série Noire adaptations of Peter Cheyney, James Hadley Chase and Mickey Spillane), but I was fast running out of reading material and on a shopping errand came across a small store just a quarter of an hour’s walk from our home, where I spotted a small digest-size magazine on sale with a Jean-Claude Forest cover illustration (this was years before he became famous for Barbarella . . . ). The magazine was called Fiction, and this was issue 56. I would find out later that Fiction was a French version of U.S. mag The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (still going today and competing with EQMM‘s sister publications Analog and Asimov’s). The cover illustrated the lead story which turned out to be the opening instalment of a serialisation of Robert A. Heinlein’s The Door Into Summer. Notwithstanding the fact that I would have to pay for the magazine from my own pocket money, I never hesitated.

Back in my room, I devoured the magazine in record time. I was hooked. I had seldom read much in the way of short stories before and hadn’t realized how much the form suited popular fiction, creating an instant in time, a world in miniature which could encompass both plot and characterisation to the fore in what was essentially a delicate and/or clever nutshell of fiction, as opposed to full-length novels which could sprawl, digress, play a game of hall of mirrors but also took a toll on reading time. This revelation excited me, and I embarked immediately on a mission to locate the previous fifty-five issues of the magazine, which I did on a limited budget, mostly in the dusty boxes of the bouquinistes along the Seine river, alongside also discovering many of the greats of genre fiction in U.S.-imported paperback originals. It took me at least two years to complete my collection, while still being first in the queue every month when a new issue was produced. I quickly graduated to the “Readers Letters” page, eventually contributing the occasional short story myself. By then I had of course also extended my collecting to Fiction’s sister publication, Mystere Magazine, which was the French franchise of EQMM.

What was wonderful about those years is that both magazines not only published the best of current short fiction and authors in the genre, but also frequent material by well-known literary figures of the present and past who had dabbled on occasion into SF and crime. Thus my education into popular fiction began, as did my rapidly spreading collector’s habit. And, needless to say, the strong desire to emulate those writers. And as short stories seemingly wouldn’t take as long to write or as much of an emotional commitment as a novel, I much preferred practicing the form. Even now, with twenty-one novels under my belt, I still get enough of a kick and satisfaction in crafting a short story.

Skip several years and I am now working in book publishing and no longer reliant on the pocket money my father dolefully handed out—a man who fought in the Spanish Civil War, on the good/losing side, and never quite understood how his offspring became something of an intellectual, despite having been sired by a man who never read a book in his life—and my collecting vice is now a full, glorious, wonderful folly. I accumulate books with a passion, across genres and the mainstream, delving when I can afford it into first editions, signed and inscribed copies, which to my utter surprise my wife doesn’t even mind. And my children, and later even grandchildren also become avid readers, which I now see as one of my greatest achievements; not that any of them would ever dare read my own books, for fear of embarrassment!

Fiction‘s long run came to an end several decades ago, but I have moved on to EQMM, which I began acquiring monthly from the 1980s and of which I promptly began hunting down back issues, alongside its sister magazines Hitchcock, Asimov’s, and Analog. (I have a complete run of Asimov‘s and Analog going back to when is was Astounding SF in the 1940s.) On a trip to one of my favourite cities, New Orleans, at a time when it still hosted a couple of handfuls of used-book emporiums full of dusty shelves and nooks and crannies, I venture into a dark and crowded antique store on Royal Street which had a few interesting Dell and Pyramid 1950s paperback originals in their window display between prints and garish vintage clothing. (A tip from collectors past: tourist cities are always good hunting grounds for old books and magazines; something about visitors invariably abandoning books in hotel rooms, I guess.) Inside, I dig out ten or so titles (mostly Rex Stout and Dell Shannon book-club editions, for which I always have a demand for in the used-book section at Murder One, my London specialty bookstore), and I am making arrangements to have them shipped to our New York shipping agent when the store owner suggests I might be interested in some old stuff he keeps at the back. He leads me to a musty storage area with cardboard boxes piled high.

By nature a pessimist, I open one of them with no great expectation only to find the carton filled to the brim with truly old issues of EQMM in rather excellent condition. I try and keep a straight face, not wanting to see the asking price rise in line with my visible interest, and move to the second and then third box. I quickly note that the actual first issue of the magazine is part of the lot as well as the very early, eminently collectable, issue featuring legendary pinup Bettie Page on the cover. My temperature rises. It turns out I am in the presence of a run of the magazine’s first twelve years, with not an issue missing. I nervously ask the store’s owner for his asking price—which turns out to be rather modest, and I have no need to negotiate. The deal is done. The shipping costs back to the U.K. will probably be as high as that of the magazines, but I am in seventh heaven.

I move on to Beckham’s which has always been a fertile territory for more used books, but the decision has already been made: the magazines will go straight onto my shelves at home and not go on sale in the bookshop. Being sole owner of Murder One has its privileges!

This was not quite the end of the story, as UPS or whichever carrier the store used then took nearly four months to transport my acquisitions from New Orleans to Queens, and I had by then drawn a line on the affair, assuming the magazines were cursed and lost in transit!

At any rate, this is how I am now the proud owner (do I hear you say hoarder?) of a complete collection of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine from its launch to the present day. In fact when I integrated the arrivals onto my shelves, there were only a couple of duplicates (which Murder One inherited and sold at an unholy profit . . .).

But you know how it goes with collectors: you never stop, even when the saner part of your mind insists and reminds you daily that it’s all a gentle kind of madness. Because it’s not just the lines and lines on the bookshelves of just EQMM, but also its sister magazines, rival publications (oh, how I treasure my runs of Black Mask, Manhunt, Dime Detective Monthly, and sundry pulps), and—reserve my place in the asylum right now—similar magazines in French. And that’s not forgetting thousands of film magazines that retrace the history of the cinema in an assortment of languages. Did I forget to mention I also collect music magazines and have a full run of Rolling Stone, Creem, Spin, and others. Maybe I shouldn’t mention the LPs, CDs and DVDs . . . should I? Yes, I do have a patient wife. Streaming or digital versions, do I hear you say? I’m deaf. Digital just cannot compete in my affections with the feel and smell of paper and print.

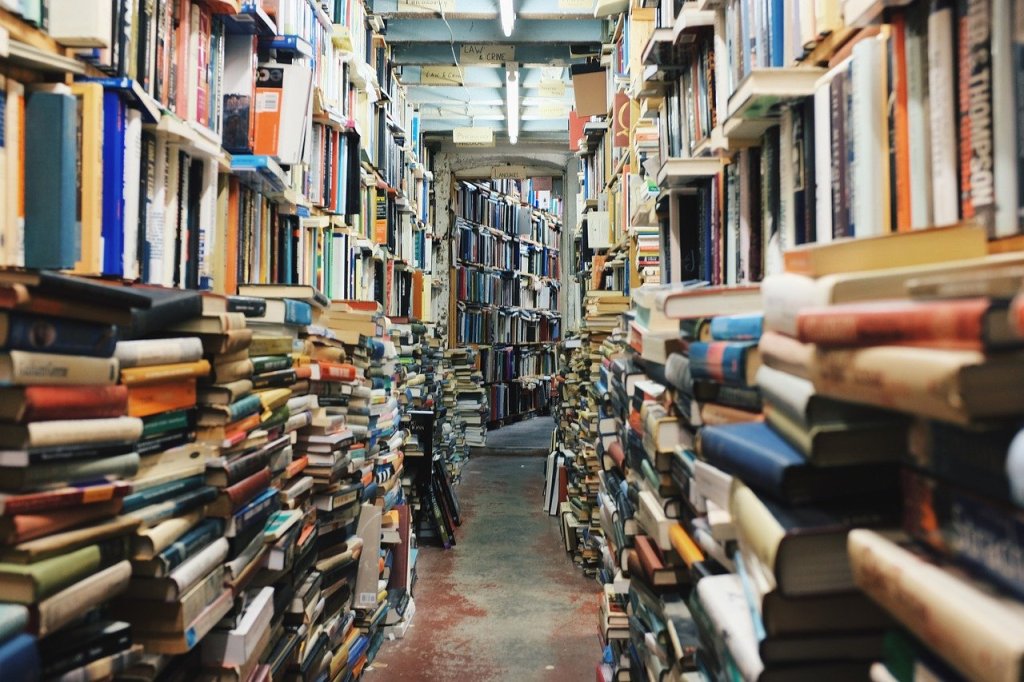

And of course I’ve made no mention of over 30,000 books at the last count (but is it my fault that publishers send me twenty or so new books a month to review or judge for the CWA Daggers?). So, yes, we have a large house, and have extended a number of times, and even built two storage buildings at the back of the garden, but still the collecting habit persists. But what compares with the pleasure of pulling an old magazine out of its sequence and dipping into it, reading again a story at random, an article, a review which will point you to an author you had hitherto been mostly unaware of? Books and magazines are my life, and I would never want it to be any different.

You might justly point out that I can’t take them with me, and that my children wouldn’t know what to do with this accumulation of material, but suitable arrangements have been made for the collection’s destinations when I must inevitably pass; they have, in my will, been promised to two university archives that specialize in popular culture.

Magazines (and books)? They made me what I am. And I proudly stand before you like on an initial visit to Alcoholics Anonymous and say, “My name is Maxim and I am a collector.”