Libby Cudmore, who made her EQMM debut with the captivating tale “All Shook Down” (in the current September/October 2020 issue), is the author of The Big Rewind, a “hipster mystery” novel that Hilary Davidson called “irreverent yet intense” and Examiner.com described as “Raymond Chandler crossed with Nick Hornby.” The author’s short fiction has appeared in PANK, The Stoneslide Corrective, The Big Click, and Big Lucks. As you’ll find out here, the author lives in upstate New York—an area that can claim other literary figures as well.—Janet Hutchings

Otsego County, NY, has a few things going for it on the literary scene. National Book Award finalist George Saunders wrote Lincoln in the Bardo from his home in Oneonta, buying research books from the Green Toad Bookstore on Main Street and wandering the Morris cemetery for inspiration. Cooperstown is the hometown of James Fenimore Cooper and the birthplace of Fates and Furies author Lauren Groff, as well as the inspiration for her novel Monsters of Templeton. Similarly, her classmate Callie Wright wrote Love All about a local sex scandal that arose from Isabel Moore’s publication of pulpy paperback The Sex Cure. I wrote my own hipster mystery, The Big Rewind on Ceperley Avenue, and “All Shook Down,” my Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine debut this issue, on Chestnut Street, one of the city’s main arteries.

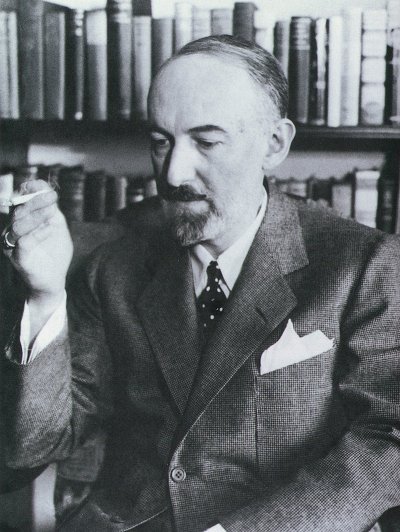

But in 2019, Oneonta added another name to list of contributions to American fiction: S.S. Van Dine.

Bob Brzozowski, the executive director of the Greater Oneonta Historical Society, began doing research on the house at 31 River Street after he was alerted that the local Salvation Army had purchased it and was planning to raze it to make a parking lot.

In researching the home’s history, he found that it was not listed on the 1890 map of Oneonta, but by 1903 was listed as belonging to H.E. Huntington & Co. Further research showed that the home belonged to Bertha and Julia Wright, the maiden aunts of Willard Huntington Wright, who based his novel A Man of Promise on Oneonta (calling it “Greenwood”), likely writing at least part of it in the home.

Wright began his professional writing career as literary editor of the Los Angeles Times, where he was the “Angry Guy Explaining Star Wars on YouTube” of his day, describing himself as “‘Esthetic expert and psychological shark,” with particular rancor about romance and detective fiction.

“The woods are full of detective stories,” he wrote in 1912, “and most of them are bad. In fact, any serious detective story is of necessity bad. It appeals to the most primitive cravings within us.”

But when he got the boot from his editing gig at the literary magazine The Smart Set in 1924 and his bitter divorce from his first wife, Katherine, he fled to his aunts’ home for a two year period of convalescence. His doctor prescribed him “light reading,” including mysteries, as part of his recovery from his “nervous condition,” – Jazz Age slang for “morphine addiction.”

Anyone who has ever been home sick and fallen into a feverish sleep in front of a rerun of Law and Order, Columbo, or Perry Mason knows the healing power of mysteries. There is something immensely comforting about knowing, as you close your eyes, that when you open them, all will be right with the world, justice will be enacted and the wicked punished.

And thus, Philo Vance–and S.S. Van Dine–were born.

Like many men, Wright read the “light” work of female mystery authors like Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers and perhaps thought, I can do that better than a lady. It was then, Brzozowski believes, he began writing The Benson Murder Case, in the bedroom of 31 River Street, published in 1926 under the Van Dine pseudonym.

The Benson Murder Case sold well, but the follow-up, 1927’s The Canary Murder Case, sold 60,000 copies in its first month, marking a distinctly American stamp on the British mystery monopoly. He would go on to write twelve Philo Vance books and several of the screenplays, where Vance was played by Basil Rathbone, William Powell, and other stars of the day.

The term “sell-out” hadn’t been invented yet, but if it had been, Wright would have certainly used it on himself.

“The fact that he used a pseudonym tells you everything about how the author was regarded and how the books were regarded,” Binghamton University professor Michael Sharp said of Van Dine in a September 2019 article in the Hometown Oneonta. “The notion that they were cheap and easy, so they were never real literature.”

But Van Dine was no copycat. As a detective, Vance used the new notion of “psychology,” as popularized by hot-on-the-scene Sigmund Freud, to give each crime scene a “signature” and draw up a profile of the likely killer rather than using a logical succession of clues. If that seems familiar, it’s because it’s a trope that has been used ever since.

Van Dine also used a “ripped-from-the-headlines” approach to his stories; “Benson” for example, was based the 1920 unsolved murder of stockbroker Joseph Elwell, and “Canary” was based on the 1923 killing of showgirl Dorothy King.

Though Van Dine lived large for quite some time, hardboiled writers like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler were soon captivating audiences, and in 1939, Wright died at the age of fifty-two, shortly before the publication of the final Philo Vance novel, The Winter Murder Case. By that point, his works were in decline, and following his death, Philo Vance was mostly forgotten.

And similarly, like too many historic homes, the Wright homestead has fallen into disrepair and has been unoccupied for more than a decade.

In 2019, the local branch of Salvation Army purchased the property, but Brzozowski’s discovery renewed public interest in historic preservation and the local connection to Van Dine’s legacy in crime fiction. The planned demolition has been held up in city planning committees, and in late 2019, Brzozowski organized a series of talks on Van Dine, including a Philo Vance film series, curated by Father Kenneth Hunter, St. James Episcopal Church.

At present, it is unknown what will happen to the house. But whether it’s restored or reduced to dust, Oneonta has claimed Van Dine–and Philo Vance–as another of our own.

Hi!

I read with much enthusiasm this article on the “S.S. Van Dine” homestead. He represents my favorite author: his quality varied, but when at his best – i.e. “The Greene Murder Case” (1928), “The Bishop Murder Case” (1929) and “The Dragon Murder Case” (1933) – there were no finer examples of detective stories, particularly as regards foreboding atmosphere (in the mid-Forties, John Dickson Carr, known as a master at creating spooky overtones in his works, selected “The Greene Murder Case” as, at the time, one of “The Ten Best Detective Novels”). I found the three cited Van Dine titles not only superb mystery fiction, but downright scary! Had not the “Dragon” case, for instance, been known as a “Philo Vance” story from the outset, it could well have been thought one of supernatural horror! I have the original Clark Agnew “Dragon” oil painting used for the cover of the initial serialization in “American Magazine”, and the dust-jacket for the Scribner’s first edition and the Grosset & Dunlap reprint; art described by detective-fiction authority, Otto Penzler, as “to die for!” I wrote a detailed article on the “Philo Vance” films for my own publication, “K’scope”, which was later selected by the Xerox Corporation for their University Microfilms project; presented a “Philo Vance” program at the Syracuse Film Convention; met a “Grant Challenge” issued by the late Hugh Heffner by providing the George Eastman House with the two scarce “Philo Vance” films specified by the publisher; and wrote the liner notes for Radio Archive’s “Philo Vance” CD collections (which can be read online with the announcement of the second box set in the series of ZIV radio programs). The author of the Edgar-winning Van Dine biography, John Loughery, upon hearing from me, lamented “Why didn’t somebody tell me about you when I was writing this!” (Forgive my lack of humility here!) So, if I can be of any assistance to you folks re: “Philo” or “Van Dine”, don’t hesitate to ask.

Enthusiastically yours,

Ray

P.S. My print of a one-of-a-kind short sound movie can be viewed on you tube; it features a “first” as regards the identity of the guilty party (this in film; not fiction). Search: THE LINE-UP [1929] – LOST CRIME TALKIE.