It’s our pleasure this week to present a post by a mystery reviewer. Over the several years during which this blog has been active, we’ve had only a couple of previous posts by members of that important profession. Elizabeth Foxwell reviews mysteries for Publishers Weekly, serves as managing editor of Clues: A Journal of Detection (the oldest U.S. scholarly journal on mystery/detective/crime fiction), and edits the McFarland Companions to Mystery Fiction series. She has received the George N. Dove Award from the Popular Culture Association’s Detective/Mystery Caucus for outstanding contributions to the serious study of mystery and crime fiction. She is also a writer of short mystery fiction, and an Agatha Award winner, whose stories have appeared in several anthologies. Her post gives a concise overview of the history of critical analysis of mystery fiction.—Janet Hutchings

Mr. Poe is a man of genius. . . . . “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” is one

of the most intensely interesting tales that has appeared for years. . .

—Review of The Prose Romances of Edgar A. Poe—No. 1,

Ladies National Magazine Sept. 1843: 107.

Although the beginning of the detective genre is traced to Edgar Allan Poe’s well-received “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841), mystery reviewing as a specialty has a much more recent history, with EQMM in a prominent place. In Dreams of Justice (2005), Chicago Tribune mystery critic Dick Adler considered NYT “Criminals at Large” and EQMM columnist Anthony Boucher to be “the man who invented mystery reviewing” (3). In What About Murder (1993), longtime EQMM “Jury Box” columnist Jon L. Breen deemed Boucher and professor James Sandoe (in the Herald-Tribune) “the best reviewers going” (ix). Although Boucher certainly made a mark in a quarter-century of reviewing, some of those predating him were Freddy the Detective author Walter R. Brooks in The Outlook, as well as mystery authors moonlighting as reviewers such as Anthony Berkeley Cox (in several newspapers), Dorothy L. Sayers (in the Sunday Times), and Dorothy B. Hughes (in the Albuquerque Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and other newspapers). (Margery Allingham reviewed “New Novels” in Time & Tide for five years, but these reviews tended to be on mainstream rather than crime-influenced fiction, with the exception of Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock.) In What About Murder, Breen also pointed out the contributions of Howard Haycraft’s EQMM “Speaking of Crime” columns of the 1940s and, in A Shot Rang Out (2008), noted the important role of mystery reviewers Avis DeVoto (best known for her work with Julia Child) and Lenore Glen Offord, as well as moonlighting author Frances Crane. New “Jury Box” columnist Steve Steinbock has noted the contributions of other “Jury Box” predecessors: locked-room master John Dickson Carr and Armchair Detective editor Allen J. Hubin. Publications such as Publishers Weekly, Library Journal, and Booklist (mostly for the library market), as well as Mystery Scene, and the sadly departed Armchair Detective and Drood Review of Mystery (for mystery aficionados), have done significant work in providing a steady critical spotlight on mysteries. The moonlighting mystery author as reviewer continues with writers such as Louis Bayard and Daniel Stashower (The Washington Post), Dick Lochte (Los Angeles Times), and Paula L. Woods (The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times)

A reviewer, said critic and Saturday Review editor Henry Seidel Canby in “The Race of Reviewers,” is a “liaison officer”: “He explains, he interprets, and in so doing necessarily criticizes, abstracts, appreciates.” Mystery author Andrew Greeley, in “Who Reads Book Reviews Anyway?,” saw reviewers’ output in a much more negative light, charging it was “mean-spirited,” “self-important, pompous and supercilious—and almost always without credentials” (7). As Marvin Lachman discussed in The Heirs of Anthony Boucher (2005), writer Robert Randisi reiterated the concern about credentials (of professional mystery reviewers vs. fans who review), and former library director Gary Warren Niebuhr noted that some authors felt that they would be better reviewers than others because they would understand books from the perspective of craft. Surely most reviewers occupy the middle ground between Canby’s saint and Greeley’s sinner, trying to do a honest job while buffeted by accusations of arrogance, bias, ignorance, myopia, and dyspepsia and often compensated only modestly for their efforts.

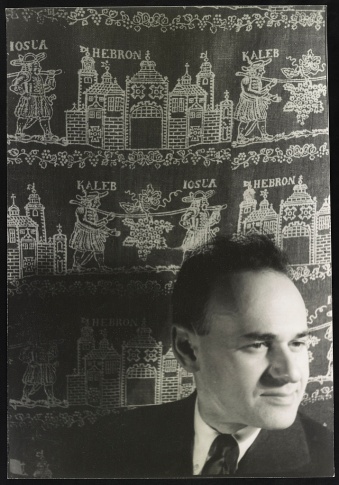

Providing straightforward and sensible signposts for mystery critics, critic Gilbert Seldes (who wrote two mysteries as Foster Johns) stated in “An Outline of Mystery”:

I like my detective stories pretty plain—a mystery, its solution, and its development; and lean rather toward Mr. [T. S.] Eliot’s strict canonical ban on mystery stories which depend on other elements. But I am convinced that a writer who knew how could involve anything from sexual passion to a passion for higher mathematics in the folds of the story itself—and so long as the story held its own way, there would be no room for protest. (100)

Gilbert Seldes, 1932

Whether the mystery under review adheres to Seldes’s “plain” path as well as holds “its own way” are the crucial questions. In reviewing, I have been disappointed by mysteries with insufficient suspects so that an obvious perpetrator is presented, uneven plotting, the tendency to tell instead of show, resolution by coincidence instead of active detection—in other words, falling short in the elements that readers expect. As an editor, I have itched to reorganize sections, tighten up wayward prose, and correct faux pas (such as a character given the wrong name in the printed book). Given this cranky litany, readers may wonder: Why do I review?

The reason lies, I think, in anticipation. What delights await? What characters will I meet? How will the author dazzle me and pull the wool over my eyes? What might I learn? Veteran reviewer Oline Cogdill noted on the Mystery Scene blog the special pleasures of reviewing mystery debuts because of their freshness and energy, and I concur; I’ve recommended two debuts for starred reviews in my nearly 10 years of reviewing for PW because they offered new and accomplished approaches to storytelling within the mystery framework. As a cofounder of the mystery convention Malice Domestic, I have an affinity for traditional mysteries (with particular fondness for the historical mystery), but this does not mean that I cannot appreciate works with a harder edge. Cornell Woolrich’s “Walls That Hear You” (1934) and Ruth Rendell’s “The New Girl Friend” (EQMM 1983) continue to haunt me years after I read them. I admire Dashiell Hammett’s efforts to reflect the real world he saw as a Pinkerton detective in his fiction and Evan Hunter’s bold experiment with Candyland (2001) in which he wrote half the book as Hunter and the other half as alter ego Ed McBain. It is an impressive form of literature that can encompass a Lilian Jackson Braun and a Donald Westlake, an Ellen Hart and a Walter Mosley, and it is the job of reviewers to try to convey authors’ triumphs as well as their missteps if reviewers are to best serve mystery readers.

Love this piece, Beth—insightful and passionate even. I think it was on your recommendation that I tracked down Ruth Rendell’s “The New Girl Friend” and that one continues to stay with me as well. And appreciate the shout-outs to my fellow Post reviewers Lou Bayard and Dan Stashower too!

Thanks, Art! I doubt you are one of the reviewers with dyspepsia. 😉