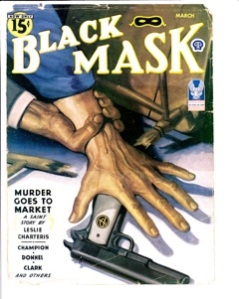

Keith Alan Deutsch is publisher and conservator of Black Mask Magazine, a publication that has a long-established connection to EQMM. He is also the co-author of several reference and scholarly books relating to Black Mask, hardboiled, and noir fiction. They include Black Mask Pulp Story Reader Volumes 1 – 6, Jo Gar’s Casebook, and The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories. His knowledge of key publications and acquaintance with many of the genre’s writers put him in a position to provide a fascinating overview of the field.—Janet Hutchings

Keith Alan Deutsch is publisher and conservator of Black Mask Magazine, a publication that has a long-established connection to EQMM. He is also the co-author of several reference and scholarly books relating to Black Mask, hardboiled, and noir fiction. They include Black Mask Pulp Story Reader Volumes 1 – 6, Jo Gar’s Casebook, and The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories. His knowledge of key publications and acquaintance with many of the genre’s writers put him in a position to provide a fascinating overview of the field.—Janet Hutchings

It is difficult to remember seventy-five years after the revolution, but Steve Fisher, Cornell Woolrich, and a few other second-wave Black Mask boys of the late 1930s ushered in a sea change in crime-fiction narration.

Fanny Ellsworth, who replaced Joseph Shaw at Black Mask in 1936, favored this change from the objective, hardboiled writing promoted by Shaw and the earlier editors of Black Mask Magazine to the subjective, psychologically and emotionally heightened writing that came in vogue under her guidance.

This little-noticed shift in style in Black Mask fiction, “The Ellsworth Shift,” led to the creation of the film genre we now know as noir through the writings of Steve Fisher, particularly in his film scripts, and through the novels and short fiction of Cornell Woolrich, whose writings we now also call noir, although the term was originally applied only to film.

This dark new style and psychology in crime-fiction narration jumped from magazine and book publications into screenplays, and led in the 1940s to the emergence in Hollywood of the classic age of the noir film thriller.

The obsessive, dreamlike narration favored by Fisher and Woolrich in their tense crime tales was a perfect match for the dark shadows and frightening, expressive camera angles developed in German and Hollywood horror cinema. Narrative fiction style and camera photography styles played against and enriched each other in the development of this new film genre.

In his seminal essay Pulp Literature: Subculture Revolution in the Late 1930s, from the Armchair Detective published in the1970s, Fisher was the first to note this paradigm shift in Black Mask Magazine fiction. The gifted new woman editor Fanny Ellsworth used Fisher and Woolrich to turn the emphasis in Black Mask away from the objective, unemotional, hardboiled writing style Hammett and the first wave of Black Mask writers introduced to the magazine, and for which Black Mask Magazine is celebrated.

Black Mask author William Brandon provides us with the most revealing portrait I know of Joseph Shaw discussing the art of objective writing in the early 1930s, when he was at the height of his influence. Brandon recounts many conversations he had with Shaw in his little-known memoir, “Back in the Old Black Mask” (The Massachusetts Review, Winter 1987):

“Shaw wanted action, naturally, as did any right-thinking pulp, but what Shaw wanted most of all was style.”

“Objectivity was part of what Shaw meant by style—a clean page, a clean line, an uncluttered phrase.”

“There was a lot of talk in those days about objective writing. Dashiell Hammett’s The Glass Key, serialized in Black Mask along about 1930, was the model of the genre. . . .”

“I remember him showing me a couple of lines in a manuscript of Raymond Chandler’s, something such as, ‘I looked into the fire and smoked a cigarette. Then I went to bed.’ This was the key line of the story, Shaw said. In those few minutes watching the fire the protagonist thought the problem through and reached his tough decision. You weren’t told that but you knew it. The line was clean, the effect was subtle but strong.”

“Objective writing was good hard prose as against the spongy prose of subjectivity. . . .”

“Even the illustrations—Shaw called them ‘end pieces’—that Shaw liked were of a certain elegance and were meant to excite the imagination rather than a surface emotion. But traditionally the pulps left nothing to the imagination, and the cruder the emotion the better. I think Shaw would have argued for hard and cruel emotion too but I think he felt it was better effected by clean and plausible and objective subtlety.”

Brandon makes it very clear that Shaw was not interested in character expressed through psychology, but only as it was expressed through external action.

Action, not character, was at the center of Shaw’s esthetic for exciting stories.

Shaw didn’t buy any of Brandon’s detective stories, but he introduced him to “Fanny Ellsworth across the hall, a pretty and witty and red-haired young woman who edited Ranch Romances (“Love Stories of the Real West”), and Fanny started buying—at rare intervals—Western stories I wrote in what I thought was a humorous vein.”

Fanny was comfortable with complexity in the stories she edited. She liked strong emotion and humor in a story, regardless of its genre.

Shaw was uncomfortable with humor, and he mistrusted complexity in his narratives, whether in plot or in psychological states.

By all contemporary accounts, Fanny Ellsworth was one of the great fiction editors of all time. Frank Gruber describes her as one of the brightest, most urbane people he met in New York. Gruber and Steve Fisher both assert that when Fanny Ellsworth took over control of Black Mask she came with a well-mapped vision for a change in the kind of crime fiction the famous magazine would feature.

She immediately started to buy stories from Gruber, who wrote lead stories for her Ranch Romances pulp, and also Steve Fisher, who she recognized had a natural talent for expressing strong and complex emotions. She also increased the number of stories she purchased from Cornell Woolrich, who also had a natural way with twisted, pathological emotional states presented in strange, dark, haunted plots.

Ellsworth quickly established a much more subjective, emotionally driven style of crime writing than Shaw. Commentators on Black Mask’s influence on film and popular culture have not often noticed these changes in style and direction.

Certainly, Curt Siodmak’s science fiction noir masterpiece, Donovan’s Brain, the darkest of obsessive, subjective, first-person narratives, serialized in Black Mask in 1942, years after Fanny Ellsworth had left, would not have made it into Black Mask if the talents of Fisher (nine stories from August 1937 to April 1939) and of Woolrich (twenty-two original stories from January of 1937 to June of 1944) had not first been let loose on its pages.

Black Mask writers and genres influenced Hollywood in more ways than hardboiled dialogue and tough-guy posturing in films based on Hammett’s, Chandler’s, and similar Black Mask writers’ popular series detectives.

The late Curt Siodmak’s work on horror films, especially at Universal scripting and creating The Wolf Man (1941), and with Val Lewton at RKO scripting I Walked with a Zombie (1943) is of interest, particularly with regard to the emergence of a noir film esthetic from out of the shadows of the “horror” films of 1930s and 1940s Hollywood (See my interview with Siodmak about his film experiences, particularly with Val Lewton).

Once the noir film emerged at the beginning of the 1940s, with the production of Steve Fisher’s novel, I Wake Up Screaming (1941), Fisher’s and Woolrich’s noir work flooded Hollywood:

In 1943, the great run of more than two-dozen noir films based on works by Cornell Woolrich, the genius of the dark thriller, began when Val Lewton produced The Leopard Man (1943): Robert Siodmak (Curt’s brother) directed Phantom Lady (1944); The Mark of the Whistler (1944) followed; Clifford Odets scripted Deadline at Dawn (1946); then came Black Angel (1946) and The Chase (1946), followed by The Guilty (1947) and Fear in the Night (1947).

Steve Fisher scripted Cornell Woolrich’s I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes (1948) with a telephone call assist from his pal Woolrich. When Fisher couldn’t come up with an appropriate ending for I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes, Woolrich suggested that Fisher resurrect the sexually obsessive, psychotic cop from I Wake Up Screaming, and turn him into the culprit, motivated by his lust for the framed man’s wife. Ironically, Fisher originally had based that haunting and haunted police detective, Ed Cornell, on his friend Cornell Woolrich.

The most famous Woolrich-inspired film, of course, is Alfred Hitchcock’s 1954 classic, Rear Window. François Truffaut’s two films based on Woolrich tales are also well known, The Bride Wore Black (1968), and Mississippi Mermaid (1969).

My aim is to mark this sea change in the esthetic of the crime thriller that started to take place in pulp fiction (and some would argue in American cinema) in the late 1930s, and which came of age in Hollywood films in the 1940s; and to note Black Mask’s, Steve Fisher’s, and Fanny Ellsworth’s role in that change.

As Bruce Eder notes in All Movie Guide: I Wake Up Screaming “opened up a whole new genre of psychologically centered crime thrillers, and also became one of the most heavily studied movies of its era.”

In Black Mask Magazine, Fisher and Woolrich shared a talent for presenting aberrant mental states, and for casting suspenseful plots with inventive incidents.

Fisher’s and Woolrich’s best Black Mask fiction set the stage for the noir revolution in popular fiction and popular film. Fisher’s novel, I Wake Up Screaming, created the blueprint, and Black Mask under Fanny Ellsworth was the inspiration, for the full emergence of the noir genre that has had an enduring impact on film and fiction in popular American and world entertainment.

Great article, Keith. On the surface, the Ellsworth era has always seemed simply inferior to the Shaw years, but you’ve convinced me it had its own strengths.

I agree this is a great article. It’s more evidence for my oft-repeated contention that the revisionist history of American detective fiction to downplay the importance of women to the field in the middle decades of the twentieth century has marginalized some important figures, not just writers but editors. I can’t resist adding that I once served on a panel with a well-known magazine editor (now deceased, and I won’t name him just in case I’m misquoting him) who said that what killed the pulps was not TV or paperback books but women editors. If we have Fanny Ellsworth to thank for Fisher and Woolrich, that’s enough to prove him wrong. But if you polled academic scholars of mystery fiction, you’d probably find most could identify Joseph T. Shaw but never heard of Fanny Ellsworth.

Pingback: » End of Summer Break.

Illuminating article, thanks very much. History seems to have favoured the fact that Shaw was there at the inception of the Daly / Hammett era and the hardboiled story and ignored her major influence in its refinement into the cinematic FILM NOIR.

Pingback: IT’S ALL ABOUT VARIETY | SOMETHING IS GOING TO HAPPEN