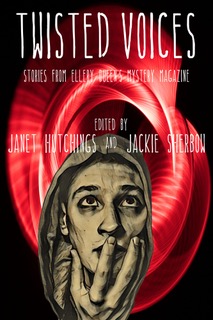

Shawn Reilly Simmons is the author of nine mystery novels and more than twenty-five published short stories, two of which have won the Agatha Award for best short story. She is also an Anthony Award-winning anthologist and the president and managing editor of Level Best Books, which she co-owns with Verena Rose. Verena Rose is Level Best’s chief financial officer and acquisitions editor. She has a particular interest in historical mysteries and has had several historical mystery stories of her own published in various anthologies. She’s also an Agatha Award-nominated editor and an Anthony Award-winning anthologist. This dynamic duo started making a mark in the field as publishers in 2015 when they took over and expanded Level Best Books, which was founded in 2003. They deserve a salute for the great work they’re doing; works published by the company have now won the Agatha, Anthony, Macavity, Derringer, and Robert L. Fish awards, and they publish everything from short fiction to historical novels to young adult fiction, true crime, and more! One of their releases this week is an anthology of stories from Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine entitled Twisted Voices, which I co-edited with EQMM’s senior managing editor, Jackie Sherbow. We’re so pleased to have this post from Shawn telling readers about it! —Janet Hutchings

As a publisher, some moments stand out as true milestones. For us at Level Best Books, our latest project represents just such a pinnacle—Twisted Voices, an anthology featuring stories from some of the most renowned mystery writers in the field. This collection, born from our partnership with the prestigious Dell Magazines, is not just a book; it’s a celebration of the mystery genre and a testament to the enduring power of short-form crime fiction.

The honor of bringing together these literary luminaries under one cover cannot be overstated. Twisted Voices: Stories from Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine pushes the boundaries of perception and storytelling. It features an impressive lineup of award-winning authors, including Gary Phillips, Joyce Carol Oates, Martin Edwards, Ian Rankin, and S.J. Rozan, among others.

What sets this collection apart is its unique focus on narrators who are integral to the mystery itself. From capers to noir tales, each story presents a narrator whose particular way of thinking affects the storytelling in unexpected ways. This approach goes far beyond the simple concept of an unreliable narrator and challenges readers to question their own perceptions and biases as they navigate each tale.

This anthology has been expertly curated by Janet Hutchings and Jackie Sherbow, two highly respected editors in the short fiction writing community. Their involvement adds another layer of prestige to this project, as they bring their deep understanding of the genre and a keen eye for quality storytelling as well as the selection and arrangement of these stories. When Janet and Jackie reached out to us to discuss a potential collaboration, we were over the moon, having been fans of theirs for so long. The wealth of talent they’ve nurtured over the years is on full display in this anthology.

For the team at Level Best Books, bringing this collection to life has been a labor of love. Each story selected represents the best of what mystery fiction can offer: ingenious plots, compelling characters, and that satisfying “aha!” moment that keeps readers coming back for more. The diversity of voices and styles in this anthology spans the full spectrum of the genre, from crooks and kids to private eyes and struggling artists.

But beyond the stories themselves, what makes this project truly special is the opportunity it provides for readers. In a single volume, mystery enthusiasts can experience the work of multiple masters of the craft, each pushing the boundaries of narrative perspective in crime and suspense fiction.

For aspiring writers, this anthology serves as both inspiration and a masterclass in short mystery fiction. Studying how these accomplished authors construct their stories, develop their characters, and build suspense within the confines of the short story format—all while playing with the concept of narrative reliability—is an education in itself.

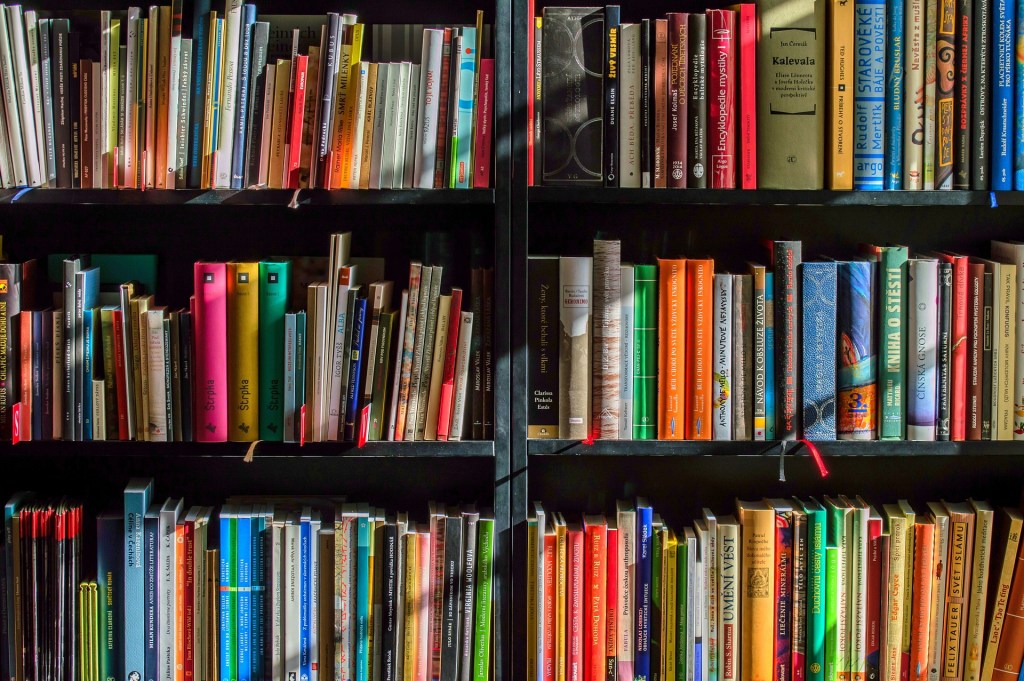

We hope Twisted Voices will find a cherished place on bookshelves and nightstands, ready to provide thrills and puzzles whenever the mood for a good mystery strikes.

Publishing this anthology is more than just a feather in our cap—it’s a dream realized. It represents what we at Level Best Books strive to achieve: bringing outstanding mystery fiction to eager readers. We’re deeply grateful to Dell Magazines for the collaboration, to the authors for their brilliant contributions, to Janet Hutchings and Jackie Sherbow for their expert editing and support, and to the readers who make projects like this possible.

As this anthology makes its way into the hands of mystery lovers everywhere, we hope it will be received as what it truly is—a love letter to the mystery genre and a tribute to the incredible writers who keep us all guessing, page after thrilling page.

Shawn Reilly Simmons is the Managing Editor at Level Best Books.