Gabriela Stiteler’s first published fiction, “Two Hours West of Nothing,” appears in EQMM’s current issue (September/October), in the Department of First Stories. A writer and educator based in Portland, Maine, Gabriela grew up in Northwestern Pennsylvania. She came to love classic detective fiction through a steady diet of paperbacks from Mystery’s Golden Age. She also came to love searching out old copies of pulp magazines and early issues of digest-sized magazines such as EQMM—something she continues to do to this day, as you’ll see in this post. —Janet Hutchings

Maybe you’re driving up the rocky coast of Maine because you’re on vacation or you live here or maybe you did at one point and you thought you’d come back because it’s the end of the summer and you’re feeling nostalgic and have time to kill. Maybe you’re listening to one of the local true crime podcasts like Murder, She Told or Dark Downeast or maybe you’ve got the windows down and you’re not listening to much of anything. You might be thinking about those distant sailboats, white pin pricks against a sea of blue, or the vacant gas station that used to sell lobsters according to a faded, hand drawn sign. Maybe you’re thinking it looks like it might rain even though the forecast promised clear skies.

Maybe you know better than to trust a coastal forecast.

Odds are solid you’ll see a thrift store or flea market or antique mall on the side of the road. The odds are slimmer that it’s open. But, if it is, do yourself a favor and stop.

Search out the tables or booths or sellers with the old magazines and pulps, sometimes in plastic wrapping, sometimes naked. You might find a copy of Suspense Magazine from 1951 with a short story by Ray Bradbury called Small Assassin, the byline of which reads, “Woman’s womb or woman’s mind, which had spawned this monster?” If you do, buy it and read the story. Think about parenting, about the two children you spawned who are mostly good kids.

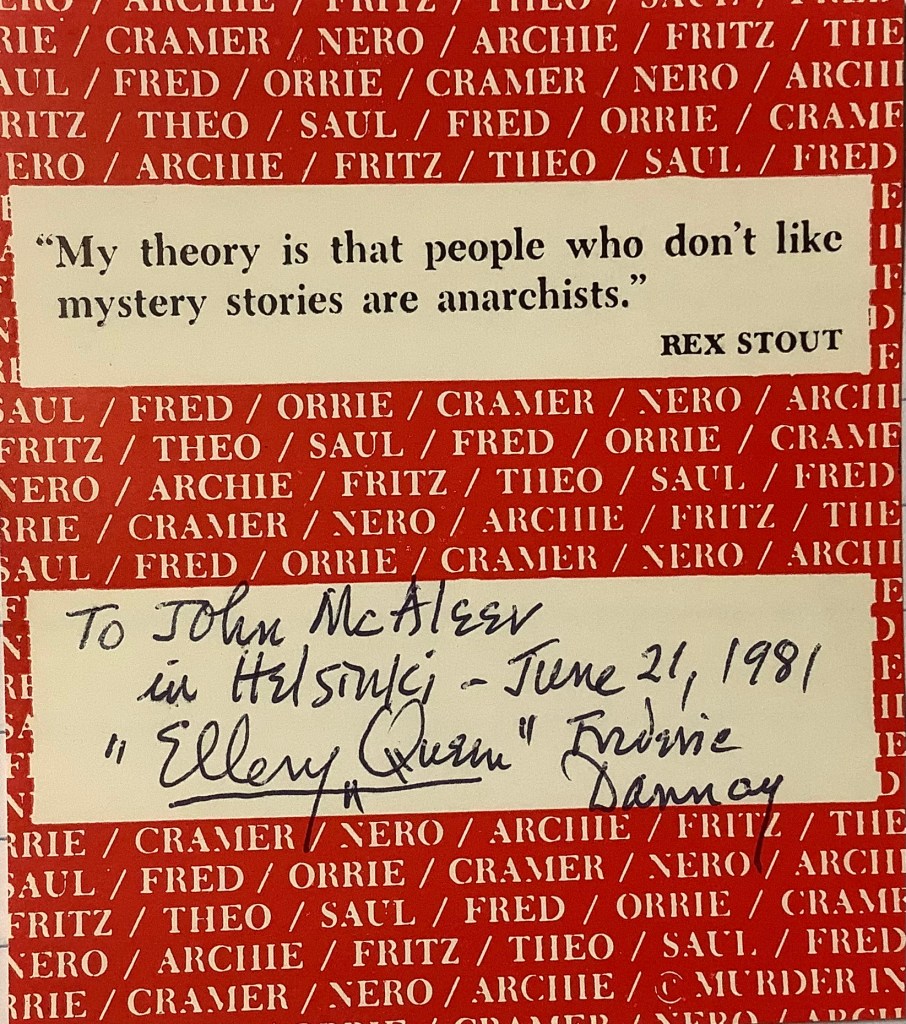

You may find an old Ellery Queen from the ‘30s with The Vulture Woman by Agatha Christie or The House on Turk Street by Dashiell Hammett. It might remind you of your Abuelita in Pittsburgh who, at ninety-five, was around for the original publication. Who, when she found out about your forthcoming story, was suitably impressed, insisting mysteries are in your blood.

Interpret that how you will.

Buy those, too.

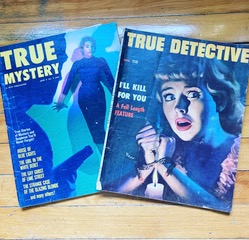

If you’re in the mood for something more sensational, search out copies of True Mystery and True Detective from the ‘50s. Maybe the guy selling them is tall and skinny and bearded from Eastport and with a tattoo of a sardine on his forearm. He’ll probably tell you he picked them up earlier that week at an estate sale and he’s not entirely sure if he’s ready to let them go because he also happens to listen to the Dark Downeast and Murder, She Told.

True Crime, he might insist, is very hot right now.

Take a minute to study the covers that have a woman in a fitted dress or almost naked or tied up or maybe, against reason, all three. Look at the advertisements on the back for Spektoscopes, which can be used for either the opera or field work, or Camel Turkish and Domestic Blend cigarettes or crossbow arrows from Sportsman’s Paradise.

Buy those from the reluctant vendor, too.

He will sell them because there are always other things men like him have their eye on.

Then, take them home or to the room you are renting or to your campsite and forget about them until it’s a Sunday and raining. Get yourself a cup of coffee or something harder if you are so inclined and it’s that time of day and you have it on hand, and sit in that chair you have by the open window. Take your magazines out of their plastic covers if they are so wrapped and spend a minute smelling them. Dusty, sour, and faintly like those old cigarettes.

It might remind you vaguely of being a kid and going through your great-grandma’s attic with your older sister who now lives in LA and is a federal prosecutor and who has always been a bit more level-headed. It might remind you of those stacks of old Life magazines in that attic on that day. Take a minute and think about the old dairy farm that was bisected by the highway system and might have been torn down. Think about your great grandma, who is long dead, and how she liked to play checkers but didn’t talk much.

When you’re firmly placed in that time of Spektoscopes and Camels and crossbow arrows, skim the titles. The Girl with the White Beret. The Strange Case of the Blazing Blonde. Hostess to Death. Lady on the Loose.

Pick one to start with and read a little more. Armed robbery is the red hot red-heads favorite sport. Or, A man may conceal illicit love but murder refuses to hide. Or, The extraordinary story of the cheerful corpse that would not stay buried.

Read the article in full. Do not be surprised when the victim is a beautiful young wife, daughter, mother, neighbor, aspiring actress, girlfriend, student, or nurse. Do not be surprised when it was the husband, boyfriend, lover, father, teacher, neighbor who did the stabbing, poisoning, suffocating, shooting, beating, or strangling.

Except in the instance of The Girl with the White Beret, in which case it was a ring of European jewel smugglers or in the one-pager about the red-headed Lady on the Loose, who was in fact the villain and confessed to twenty-five armed robberies.

Think a little about how the stories are predictable in their brutality and how at the end there is a vague sense of justice in a rather bleak world. Then finish your coffee, or whatever you decided to pour and put the magazines back in their plastic sleeves until the next time it rains.