Lori Rader-Day is the Edgar Award-nominated and Agatha, Anthony, and Mary Higgins Clark award-winning author of The Death of Us, Death at Greenway, The Lucky One, Under a Dark Sky, and other novels. She lives in Chicago, where she co-chairs the crime fiction readers’ event Midwest Mystery Conference and teaches creative writing at Northwestern University. Her latest story for EQMM, “[The Applause Dies],” appears in our current issue, September/October 2024. In this post she takes up an important topic that doesn’t get covered much on this site. —Janet Hutchings

I hate instruction manuals. I hate the make-ready work ahead of just about anything. I would rather leap into the center of something new and figure it out. That’s how I wrote, too—until a book project forced me into a new role—triumphant researcher!—and paid me back with some of the best experiences of my writing life.

Writing Up to the Unknown

As a writer, I’ve always gone the “organic” route, writing myself into a character and story, then digging myself back out again. As a road map, I used my inner sense of how a story moves—gained from being a voracious reader, of course—and my own preference for how information is unveiled. When I hit roadblocks that required research, I learned to type in “XXX” and keep moving. Those XXXs were the purview of some future Lori, who would surely figure out a workaround.

This was bad news for the Lori who later discovered, upon typing “The End” into the draft of her first novel, that she still had some XXXs to see to.

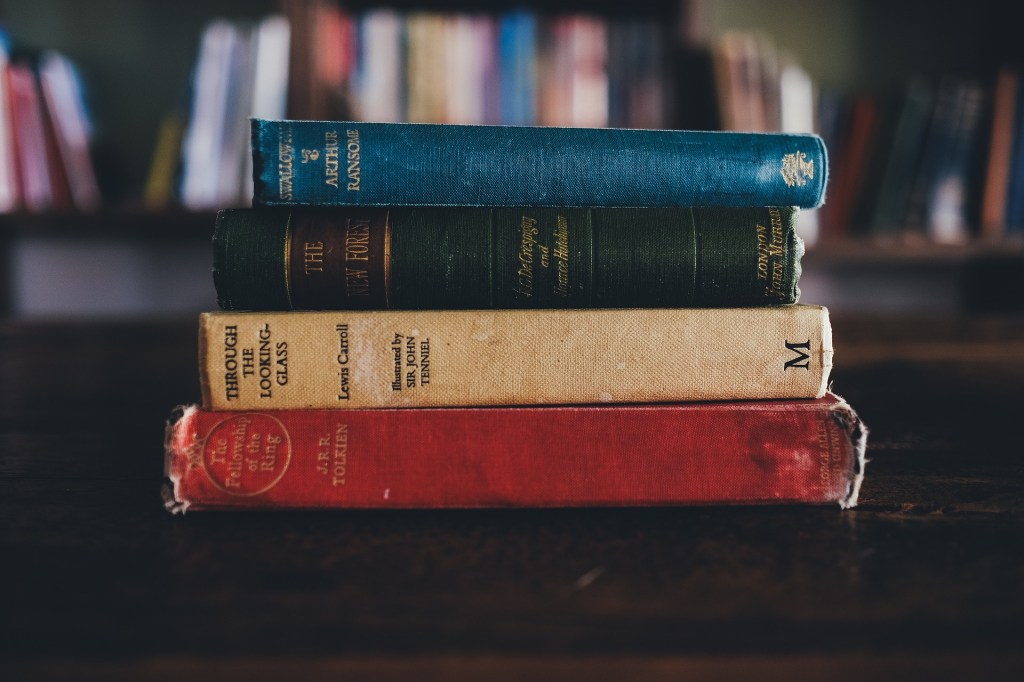

The answer to that series of Xs I’d typed into my first novel, The Black Hour, was found by reading a chapter in a sociology textbook about violence. My old friend reading! Books are always the first research step, because if someone has already gathered resources, culled the information, and distilled it all into a few hundred pages, that’s a rich vein. A good place to start, anyway, and in fact for my third novel, The Day I Died, the entire idea for the book came from spotting a book on the shelf I hadn’t been looking for: Sex, Lies, and Handwriting: A Top Expert Reveals the Secrets Hidden in Your Handwriting by Michelle Dressbold.

But sometimes it’d just not possible to find what you need to know by visiting the library.

Some writers don’t worry about research, of course. Make it up! It’s fiction! And of course we do make up a good deal.

When we’re “making things up,” though, we’re pulling from our own experience, even if we have to extrapolate a bit. If our experience doesn’t help us with a character or situation, the next best thing is to solicit the help of someone whose life experience or earned knowledge parallels the character’s life better. An expert. Imagination is great, but confirmation is better. And while I usually write about places I know really well, I learned that I can make myself a bit of an expert on the world of my story with on-the-ground research. Are you keeping track? All those XXXs of unimaginable, unfudgeable unknown can only be replaced by some combination of Experience, Experts, and X-marks-the-spot. When we want to make sure our stories don’t make us numbskulls to the readers who know, we work harder to get it right.

Getting It Wrong

On-site research is essential but I didn’t understand that at first. Up until my fourth novel, I had been borrowing story settings from places I knew: the university campus where I worked, a hotel in my hometown, a chain of lakes in Wisconsin I’d been to many times on vacation. When I decided to write about a dark sky park for what would become Under a Dark Sky, I wanted to visit a place where artificial light had been controlled for the experience, but none of the official dark sky places designated (at the time) by the International Dark-Sky Association were within six hours of Chicago. I chose as my model the nearest of these properties, the Headlands Dark Sky Park, way up in the fingertips of the Michigan mitten—and then winter set in. I was forced to write a draft of the book without getting to the park myself.

The next year, while the book was still in draft, I was finally able to drive through Michigan all the way to the furthest reach of the lower peninsula and visit all the landmarks of my book—and thank goodness I did.

I’d left in two artifacts of writing without a net that definitely would have lost all Michigan readers. The first is that I had my Chicago-residing protagonist driving through . . . Lansing.

You may not understand why that’s not right, but everyone in Michigan did, when I told this story to a gathering of four hundred people at a library fundraiser in Grand Rapids. As a body, the entire room leaned back and gasped.

“I changed it!” I yelled. “I swear! I changed it!”

(It’s Grand Rapids one would drive through to get between Chicago and northern Michigan.)

The other artifact was that I’d placed my protagonist in this far-north park without mentioning that she would have seen the Mackinac Bridge on her way into town. The Mighty Mac connects the tip of the lower peninsula of Michigan, the mitten, to the upper peninsula. The bridge is visible ten miles out, a beacon that no first-time visitor would ever miss.

I swear I changed it.

Getting Close to War

When I decided to attempt my first historical novel, then, I knew I would have to dig in. The inspiration for the novel was a little-known historical fact: During World War II, when millions of children were evacuated out of London and other metro areas into the countryside and away from what would be called the Blitz, ten children were quietly placed at Agatha Christie’s beloved summer home, Greenway.

Is it any wonder I had to try?

For research, I turned first to books, tracking down the only handful of published references to this episode, including the two or three sentences Christie offered in her own autobiography. Part of my research was reading the books Christie published right before, during, and right after the war, and the titles where she had fictionalized Greenway herself.

Then I moved onto the dusty records, thankfully less dusty in digital form within Ancestry.com, tracking down the names and any details I could learn about the people in Christie’s household, on the estate, and in the community. I enjoyed some true research victories doing this work, returning the names of Christie’s butler and cook, a married couple the Christie estate couldn’t confirm, and proving once and for all the names of the couple who chaperoned the group of children to Greenway—and sending that proof back to estate, so they would have it for their records.

I traveled to Greenway in 2017 as a tourist, seeing what there was to see that connected the house to that group of evacuees. There was little, except one cupboard kept behind a locked door. Inside the cupboard, the shelves were still marked with the names of five of the children: Doreen, Maureen, Pamela, Beryl, and Tina.

I had had a lot of doubts that I could tackle this story. I was American. I was not a historian. And research . . . well, we’ve covered that. But in that moment when I spied those names on the cubbies that had held their shoes, clothes, and photo albums so they wouldn’t forget their mums and dads, this story became mine. This history wasn’t ancient history, those names on the cubbies told me. This history was within reach, and it was human. And it had never truly been told. I couldn’t make it up. In the same moment the story became real to me, I also realized I would have to do my best to gather the facts.

I wrote a (bad) draft, and then went back to Greenway in 2019, knowing now what research I needed to finish the story. I needed to live at Greenway, to breathe its air and walk its grounds and poke around in its hidden spots. To stand on the hill as Agatha would have done. To know what its night sounds were, how dark it got, to understand how it would have felt to be isolated there, away from family, while bombs dropped on the river, and on the too near Channel. How close the war would really have been.

Writing Death at Greenway was a wild swing for me, but if I was going to try, then I had to put myself in that house. I had to know what the children had experienced. On this one piece of history, they were the only eye witnesses who might still be alive. They were the true experts—

Which leads me to Doreen.

Finding the Human in History

In the course of my research, the staff of the National Trust, who now own the house and operate it as a tourist site, turned over a copy of a letter written to them by one of the children—Doreen, from the names on the cubbies. Her letter recounted everything she remembered about being evacuated to Greenway during the war. With a little Facebook sleuthing, I located her son and got in touch. She’s eighty-six in November, and we still write letters. Her friendship is the sort of charmed result that I couldn’t have even known to hope for when I set out on this project. She also made clear to me that though this was a story about war, her time at Greenway had isolated her from it. She had felt safe there, and loved. That’s not the typical war evacuee story. If I had never talked to Doreen, I might have got that one very important detail wrong.

We say that writing must be its own reward. Publishing is punishing, but writing can be the thing that keeps you connected to your best self and to the world around you, to gratitude, to human experience.

Research is the same way. Where it had always seemed to me that research was homework I never asked for, drudgery, now I understand it to be honest work, rewarding, and connecting. It’s a chance to learn, experience, and to live lives beyond our own, which is exactly why we read novels in the first place.

History is human, just like stories. Sure, we could make it all up. But what would be the fun in that?